Kinship and Migration

The African American Population in Lafayette after the Civil War

By Mary E. Anthrop

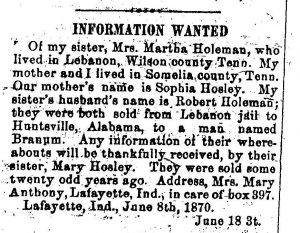

A “Lost Letter” from the Christian Recorder (Philadelphia)

Curious notices, like the one above, appeared frequently in the African Methodist Episcopal Church newspaper, The Christian Recorder, in the years at the end of the Civil War. Known as “Lost Letters,” the notices describe the determined efforts of freedmen to reconnect with relatives. While it is not clear, if Mary Anthony of Lafayette found her sister and brother-in-law, the inquiry testifies to the strong bonds of kinship or family ties among the formerly enslaved. Kinship ties might also have played a role in the migration patterns of freedmen.

Emancipation, for the formerly enslaved, provided the choice to move about freely. Border states quickly experienced the arrival of new residents. Indiana was no exception to this migration. Between 1860 and 1870 Indiana’s Black population grew from 11,428 in 1860 to 24,560 in 1870 and rose to 39,228 by 1880. Tippecanoe County’s Black population grew from 143 in 1860 to 172 in 1870 and to over 300 by 1880.

Prior to the Civil War most of Indiana’s African American residents lived in rural communities throughout the state. After the Civil War, new Black residents settled in Indiana towns and cities, at first in the border towns along the Ohio River. Tippecanoe County was an exception to this trend. Its African American population had been an urban community before the Civil War. After the Civil War, Tippecanoe County experienced both an urban and a small rural African American population growth.

The hope of economic betterment encouraged a wave of new migrants to resettle in Indiana. With little resources after generations of enslavement, most Black migrants came from the nearby states of the Upper South. Before 1900 one-third of Indiana’s African American population claimed Kentucky as their place of birth. Tennessee represented 6% of the African American population(1).

Kinship also might have played a role in determining the destination of the new Hoosier residents. The family stories of John and Abel Fields from Kentucky and the Edwards and Smith families from Tennessee could be anecdotal evidence of this argument.

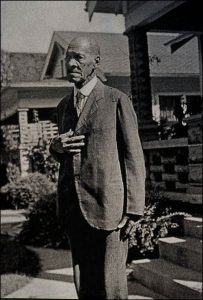

John Fields (1848-1953) was born in Owensburg, Kentucky. In a 1937 Depression Era WPA interview he testified that he was one of twelve children. He also described the break-up of his family before the Civil War.

When John Fields was a child his master died. To settle the estate, all of the enslaved persons on the plantation were sold. The heirs wrote their names on pieces of paper, and put the slips into a hat. The individual Black workers then drew out the names of their future owners. Fields drew the name of a relative of the master who was a widow.

John Fields described the family break-up as one of “… heart-break and horror….” At six years old Fields never saw his mother for longer than one night. His mother’s owner allowed her only one week during the year to visit all of her children. He reported that five sisters and two brothers went to Charleston, Virginia; one brother and one sister to Lexington, Kentucky; one sister to Hartford, Kentucky; and another brother stayed with him in Owensburg, Kentucky.

When John Fields realized he was free in 1864, he and his brother resolved to run away to join the Union Army. While his brother joined the Union Army, the Federal officers rejected John as too young for service. He next travelled to Evansville, Terre Haute, and Indianapolis. As a laborer, he settled in Lafayette by 1869.

In 1872 John Fields married Elizabeth Scott, a former enslaved person and a native of Georgetown, Kentucky. John and Elizabeth had four children. Together the hardworking couple acquired three properties in Lafayette. His 1953 obituary remembered him as a civic-minded citizen, sponsoring local fire fighters, and a devout lay preacher, being a charter member of the Second Baptist Church.(2)

John Fields independently crafted a successful life for himself and his family. Ties to his birth family, despite the early separation, seemed to remain strong. Lafayette newspapers referenced a brother Abel and his twin Cain living in Kentucky. In addition John’s good fortune might have inspired Abel to move to Lafayette. Abel Fields (1850-1928) migrated to Lafayette by 1881.

In 1889 Lafayette Journal articles lauded the entrepreneur efforts of Abel Fields. Abel came to Lafayette as a poor man. Through hard work he amassed enough money to launch a grocery business. By 1883 he had purchased property on Spencer Street in the North-End of Lafayette. He operated this grocery business for nearly forty years. The Lafayette community also knew Abel as the official and faithful winder of the Tippecanoe County Court House clock for over twenty-five years. At the age of seventy-eight Abel returned to his Kentucky home and died there in September of 1928.(3)

Data gathered from city directories, census records and newspaper articles suggest that family ties encouraged the resettlement of the Edwards and Smith family members from Tennessee to Lafayette. Marcus Edwards and Aquilla Smith originally lived in Wilson County, Tennessee.

Notes from the “News of the Colored People” columns (12-27-1879, 1-24-1880) of the Lafayette Journal reported that Aquilla Smith, a young man in his mid-twenties, travelled to Lebanon, Wilson County, Tennessee to visit friends and relatives. He stayed nearly a month in the South. Aquilla Smith, at the time, worked as a janitor at the Lincoln Club. Within the next year, according to his 1915 obituary, Marcus Edwards walked from Wilson County, Tennessee, to Lafayette. Edwards, a Civil War veteran, travelled a route of 436 miles; he worked in the different towns along the way. For many years he was a teamster in Lafayette.(4)

Interestingly Marcus Edward’s sister, Delia of Wilson County, was married to a David Smith (a relative to Aquilla?). The couple and their children lived in Lafayette by 1885/1886. David died of consumption in 1887. Delia Smith, who worked as a laundress, raised not only her children, but saw that four of her grandchildren (orphaned children of Emma Smith and Louis Silance) graduated from Jefferson High School and Purdue University. Delia Smith died in November of 1931.(5)

Additional members of the Edwards family of Lebanon, Wilson County, Tennessee, also moved to Lafayette. Two other sisters of Marcus, Rebecca (1845-1922) married to John Seals, and Fannie White (1856-?) lived in Lafayette by 1900. Priscilla Edwards (1810-1902), the mother of Marcus, Rebecca, Fannie and Delia, also of Wilson County, Tennessee, died in 1902 in Lafayette. She was 92 years old and had been enslaved in the South.(6)

There is no surviving testimony, as yet discovered, from the Fields, Edwards, and Smith families on their reasons for selecting Lafayette as a new home after the Civil War. Economic betterment likely prompted their move to the North. Initial success by the first family migrants to Lafayette and strong kinship ties could have encouraged the resettlement of their other family members.

[1] Emma Lou Thornbrough, The Negro In Indiana before 1900, (Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1985), 206-230. [2] To read more of John Fields 1937 interview see the collection: Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936 to 1938 at: https://www.loc.gov/item/mesn050/

“Slavery-Born John Fields, Oldest Resident Dies at 104,” Journal and Courier, February 7, 1953.

[3] “Third Anniversary,” Lafayette Journal, September, 1889; “Lafayette Abroad,” Morning Journal, December 17, 1889; “Loved His Task,” Journal and Courier, August 1, 1928; and “Death Claims Former Slave Grieving Over Loss of Job,” Journal and Courier, September 12, 1928. [4] “Marcus Edwards,” Lafayette Journal, March 29, 1915. [5] “Mrs. Delia Smith, 83, Born in Slavery, Dies At Family Home Here,” Lafayette Journal and Courier, November 17, 1931. [6] “Priscilla, Edwards,” Lafayette Daily Courier, July 23, 1902.