A Privileged Education in Post Civil War Lafayette, Indiana: The Schooling of Alice J. Earl

By guest blogger Mary E. Anthrop

A frequent entry in Alice J. Earl’s 1867 diary was the simple notation – “went to school.”(1) In the pocket size leather covered diary, cared for by the Tippecanoe County Historical Association, Alice J. Earl, daughter of the wealthy entrepreneur Adams Earl, penciled a record of her daily activities. The teenager’s notes of two or three phrases or sentences reveal post-Civil War educational and cultural offerings. By the late 1860s upper middle class Hoosier families provided for their children in a comfortable fashion and gave them unprecedented learning opportunities.

Alice Jane Earl was born in Lafayette, Indiana on October 20, 1850 to Adams and Martha J. Earl. Two years later her brother Morrell was born. Adams Earl, a native of Ohio, was one of Lafayette’s earliest and most successful businessmen. In 1857-1859 Earl built a seven room Italianate mansion at Earlhurst or Fountain Grove, a ten-acre home site complete with a deer park, north of the city. By 1870 his diverse success in mercantile, banking, beef and pork packing, grocery, railroad and agricultural enterprises allowed Earl to accumulate real estate valued at $600,000 and $200,000 in personal wealth.

Alice Earl never identified her school by name in her 1867 diary, but she left clues in her references to her and Morrell’s teachers. Lafayette city directories and newspaper advertisements of private schools lead to the identity of their school.

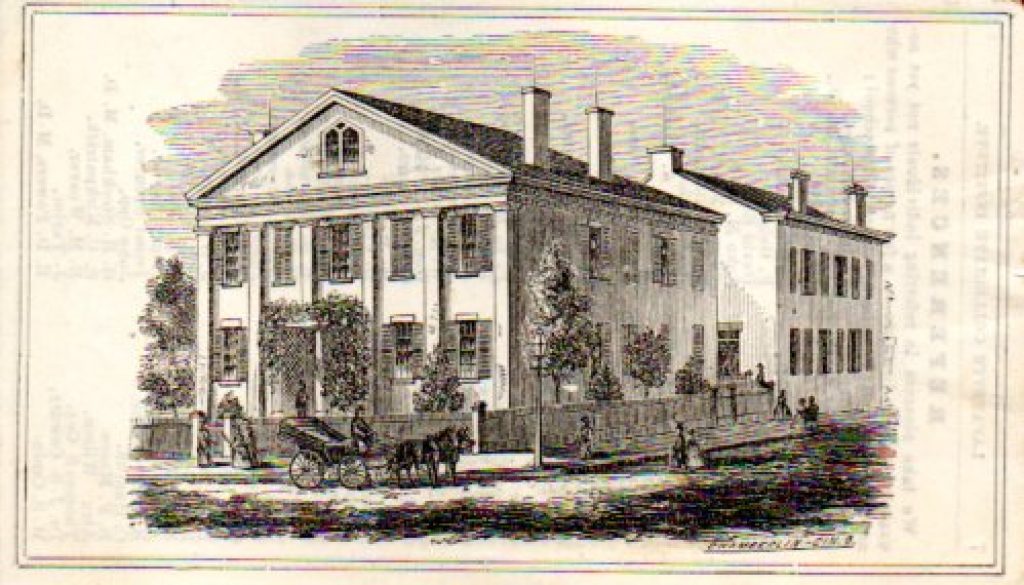

Lafayette boasted of a variety of educational institutions in 1867. Although the public school system struggled to emerge in the decade before the Civil War, by 1867, the city provided free education in four buildings. Several religious denominations, including the Catholic, Jewish and Lutheran populations, operated academies. The African Methodist Episcopal Church provided a school for its community before having access to the public school fund in 1869. Independent academically trained individuals also established schools in rented church spaces or large dwellings. Adams Earl enrolled his children in one of these private establishments; Alice and Morrell attended the Lafayette Collegiate Institute. In 1864 Ira W. Allen and his wife opened a primary, preparatory and collegiate school for boys and girls in the Greek revival former residence of Henry L. Ellsworth.

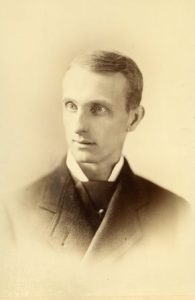

Ira W. Allen (1827-1912), an imposing figure who stood over six feet tall, graduated from Hamilton College, Clinton, New York. He continued his studies for the next two years in Europe, and then moved West to accept an offer to teach mathematics at Antioch College in Ohio in 1852. He was also among the organizers of Union Christian College in Merom, Sullivan County, Indiana in 1858. After marrying Lydia Reed Ford of New York in 1863, he moved to Lafayette. A dedicated and ambitious educator the Lafayette Journal endorsed him for the position of Indiana Superintendent of Public Instruction in 1868 – “Practical, cultivated to an extraordinary degree, familiar with all the latest and best educational ideas and systems, in the prime of manhood, of easy address, and terse and forcible in diction, we know of no one who is so well qualified….”(2) When the Lafayette public schools improved, the Lafayette Collegiate Institute closed in 1870. The Allens moved to Chicago where Ira conducted the Allen Academy until 1893.

According to the First Annual Catalogue of Lafayette Collegiate Institute from 1864-65, the Allens promised to “furnish the mental growth and discipline necessary to fit young women for the responsible duties of society”(3) and provide course instruction for boys interested in business occupations or university admission. A proscribed course of study relied on classes in English language, composition, elocution, Latin, history, geography, and mathematics. Side courses included Greek, French and German languages, bookkeeping, surveying, civil engineering, art and instrumental instruction.

With a slightly higher enrollment of girls, Lafayette parents enrolled 221 students during the Institute’s first year. At first Alice and Morrell Earl enrolled in the preparatory department and by 1867 Alice advanced to the collegiate department. The school’s 1867-’68 prospectus described a graded system that employed the progressive Pestalozzian or object method of instruction, a method that opposed memorization learning, proposed learning based on the child’s individual development and encouraged the use of tactile objects and concrete experiences. This concept laid the foundation for today’s modern elementary education.

The Allens encouraged homework and recognized the need for physical exercise. The prospectus noted that students benefited from exercise in the walking to and from the Institute in addition to their performance of home chores. Alice attended school regularly and even occasionally walked the almost two miles from the Lafayette Collegiate Institute to Earlhurst. On February 26, 1867 she wrote: “I walked home from School for the first time this winter.” The Allens provided some apparatus for practicing calisthenics and gymnastics.

Although the Institute did not adhere to any one particular Protestant sect, the Allens believed children with strict religious principles advanced more thoroughly in their studies. Discipline appealed to the moral sense of the children. Alice in March 28 wrote: “Prof. Allen sent William Underwood home from School for making fun of Religion in his essay.”

The Allens also advocated parental involvement in their child’s education, such as, not allowing their sons and daughters to attend amusements during the school week. Notes in Alice’s diary referencing lecture and theatrical attendance suggested that the Earl family did not always follow the school’s guidelines. As a mid-size city Lafayette boasted of an “opera house,” as well as, large and accommodating churches, which supported religious revivals and popular lectures. Lafayette’s location on the railroad lines not quite halfway from Indianapolis to Chicago allowed for theatrical celebrities to agree to occasional performances.

While admission prices of 50 cents or a dollar, prohibited many working class families from attending public amusements, the Earls almost weekly attended a lecture or theatrical performance. Alice heard in early January of 1867 Rev. O.H. Tiffany of Chicago speak on “The New Civilization – Shams and Shoddy – Philosophy of common sense – Work and its worth,” in March John B. Gough, a reformed drunkard, deliver a mesmerizing autobiographical fall and rise to sobriety temperance lecture, and in April civil rights leader Frederick Douglass promote the cause of universal suffrage. Alice also attended a vocal concert of the Alleghanian Bell Ringers and enjoyed the dramatic readings of Alf Burnett, an elocutionist. In June Honorable Schuyler Colfax, then Speaker of the House of Representatives, delivered a benefit lecture in Lafayette for disabled soldiers and seamen and their families. Alice attended Colfax’s evening presentation – “Across the Continent,” a promotion of the United States destiny in the West.

Alice preferred, however, theatrical celebrities and amusements. In January she noted that the Italian tragedienne Adelaide Ristori, on her first tour of the United States, would pass through Lafayette on her way to an engagement in Chicago. In the spring she attended performances of the melodramas The Stranger, The Elopement and Rosedale, starring Lawrence Barrett, a Shakespearean fellow actor of Edwin Booth, and before the Lafayette Collegiate Institute suspended classes for the summer she heard the British operatic soprano Euphrosyne Parepa-Rosai and saw three different performances by European operatic stars Felicita Vestvali, the “Magnificent,” and her cousin Vestvali Lund.

The Lafayette Collegiate Institute’s school year commenced in September and closed in June; the tuition for each of the four quarters ranged from $7 to $8 in the primary department to $15 in the higher classes of the Collegiate Department. The Allens justified the cost of their instruction when they noted the heavy expenses of the school. They quoted as truth the educator’s adage that “the best instruction is always the cheapest”(4) and ‘there is nothing on earth as precious as the mind, soul and character of the child.”(5) The Lafayette community gave their approval of the Institute in a Report of the Examining Committee in June of 1865. “We find the school under most able and efficient management and exceeding well-ordered in all its departments…. The Institute needs only the patronage it so richly deserves to make it the pride of the city and a source of untold blessings to the rising generations.”(6) Alice Earl’s uncle, Moses Fowler, President of the National State Bank, was President of the trustees. The Allens also listed in its catalogue and prospectus other successful businessmen (including Adams Earl), lawyers, doctors, and ministers in Lafayette as patrons of the school.

Alice’s frequent references to social activities indicated a less that serious approach to her studies. Alice enjoyed the peer social encounters associated with school attendance. She noted: “Lizzie Gordon made a wish with my large gold ring, I am not to take it off for a week from today” (January 10, 1867 diary entry) and “Louie P. my seatmate is not here today and I feel rather lonesome without her.” (January 23, 1867 diary entry) School provided the contacts for engaging in after school activities, including: Valentine exchanges, sleigh and horseback riding, collecting wild flowers, playing croquet and attending the then popular dancing parties. On January 11, 1867 Alice wrote: “At a party at Mollie Orth’s had a very pleasant time. Danced until two o’clock. Henry Taylor and Lizzie Chesnut fell down.”

Alice mentioned several subjects she studied at the Institute, including: geography, arithmetic, French and algebra, but her only reflection on school was the ambiguous comment she wrote on the first day of a new term in January. On January 28, 1867 she penned: “I intend to be a better girl than I have been in the past.” Only a few days before on January 24 she noted: “Lou P. (her seatmate) and myself had to remain a while after school.”

The Earls also provided for Alice’s educational experiences beyond the private school classroom. Alice regularly attended the Second Presbyterian Sunday School and several times a week received piano lesson instruction from Professor Frederick W. Miles of the Lafayette Collegiate Institute. Alice purchased books for reading pleasure, such as The Cameron Pride (1867) and The Homestead on the Hillside (1855) by the popular and prolific sentimental fiction writer Mrs. Mary James Holmes. Alice also noted in a March 25, 1867 diary entry: “Pa bought the American Cyclopedia 21 Vols. Last Saturday. Gave me a large book of Shakespear.”

Adams and Martha Earl, however, planned different educational experiences for their son Morrell. Alice’s diary revealed that Morrell did not attend the Institute’s final quarter in the spring of 1867; the Earls sent Morrell to work on the Shadeland Farm, land Adams Earl purchased from the estate of Martha Earl’s parents. Like Earl’s land holdings in Benton County, the Shadeland Farm raised hogs and sheep and grazed large cattle herds. Preparing Morrell, his only son, to take over family business interests prompted Adams Earl to diversify Morell’s educational experiences with practical as well as academic opportunities. Later Morrell attended Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana. Alice’s reference to Morrell’s absence at the Institute marked the only time Alice noted a household chore. She had to take care of his chickens while he was away from home!

None of Alice Earl’s diary entries for 1867 hint at an upcoming change in her educational experiences. In September of 1867 the Earls enrolled Alice in the Rockland Female Institute (1856-1880) in Nyack, New York. Alice and her cousin Annis Fowler joined Lafayette natives J. Elma O’Ferrall, the daughter of Robert M. O’Ferrall, physician and businessman, and Altha W. Reynolds, daughter of William F. Reynolds, mercantile and railroad investor, at the Rockland Female Institute. Both O’Ferrall and Reynolds patronized the Lafayette Collegiate Institute and the girls’ siblings were classmates of Morrell Earl.

Academic achievements from the daughters of social and business acquaintances perhaps lured the Earls to send their teenage daughter nearly 800 miles away to an expensive boarding school. The forty-two week academic year cost $400 in annual tuition and boarding with additional charges for extra lessons and comforts.

Alice Earl’s diaries and letters testified she attended the Rockland Female Institute for at least three years, 1867-1870. Although Alice noted in her 1870 diary that she was on the roll of honor, whether or not she graduated from the Rockland Female Institute is unclear. A January 23, 1870 diary entry read: “Pa told me in his letter yesterday that if I studied hard all this year. I need not come next year.” Cousin and classmate Annis Fowler, however, performed with honors and was one of eleven graduates from Rockland in 1871. The Rockland County Journal on June 24, 1871 noted that her delivery of her essay, “Westward Ho” … was characteristic, having the true Western dash and vigor, chastened with the grace of Eastern culture.”(7) Annis’ younger sister Ophelia and Ada Ellsworth, daughter of the late Henry W. Ellsworth of Lafayette, an owner of the Lafayette Courier and minister to Norway and Sweden, later enrolled in Rockland.

After a short time at Miss Hinsdale School on Madison Avenue in New York City in 1871, Alice J. Earl returned to Lafayette. In 1876 she married attorney Charles B. Stuart of Logansport, Indiana. The couple took up residence in Earlhurst and when Morrell died in 1879 of typhoid, they assumed more of the responsibilities of the Earl interests in banking and agriculture of Benton and Tippecanoe Counties.

Adams and Martha Earl, as did other well-to-do Hoosier families after the Civil War, provided enhanced learning and cultural opportunities for their children. Those educational advantages included advanced academic studies at private institutions, like the Lafayette Collegiate Institute and Rockland Female Institute in New York. Parents purchased books for their children’s pleasure reading, as well as literary classics and scholarly works. Their children attended civic and cultural events and participated in religious instruction. These opportunities, out of the reach of most working families, also encouraged social interactions and connections with other children of successful parents. These advantages prepared children for the responsibilities of running family’s businesses; the well-to-do families also established a socio-economic elite society for another generation. After the death of her husband in1899, Alice J. Earl, for example, became one of the directors of the First Merchant’s National Bank and operated the Shadeland Farm. With her widowed sister-in-law and classmate friend, Ada Ellsworth Stuart, she also turned her attention to community and civic causes. Both women championed progressive causes, such as women suffrage, in the early 1900s.

For additional reading see: Marshall, Joan E. “The Changing Allegiances of Women Volunteers in the Progressive Era, Lafayette, Indiana, 1905-1920.” Indiana Magazine of History 96 (September 2000): 251-285. and Sutherland, Daniel E. The Expansion of Everyday Life 1860-1876. New York: Harper and Row, 1989.

(1) Diaries of Alice J. Earl, (January 1, 1867-August 1, 1867 and January 1, 1870-March 16, 1870). Adams Earl Family Collection. Tippecanoe County Historical Association. Lafayette, Indiana. (Unless otherwise noted, all diary quotes are found in the 1867 diary).

(2) “Professor Allen, of Lafayette.” Lafayette Journal in Indianapolis Journal, February 19, 1868, p.1.

(3) First Annual Catalogue of Lafayette Collegiate Institute for 1864-65. Lafayette, Indiana: Jas.P. Luse and Co., 1865. Indiana State Library, Indianapolis, Indiana, p.15.

(4) Circular for 1867-8 of the Lafayette Collegiate Institute. Tippecanoe County Historical Association. Lafayette, Indiana. p.6.

(5) Ibid.p.7.

(6) “Report of the Examining Committee,” June 16, 1865. First Annual Catalogue of Lafayette Collegiate Institute for 1864-65. Lafayette, Indiana: Jas.P. Luse and Co., 1865. Indiana State Library, Indianapolis, Indiana, p.19. Also see “The Examination of Classes at the Collegiate Institute,” Lafayette Daily Courier, January 27, 1866 and Lafayette Collegiate Institute, Lafayette Daily Courier, June 14, 1867.

(7) “Commencement at Rockland Institute,” Rockland County Journal, June 24, 1871.