Clipping, Collecting and Pasting:

Assembling Scrapbook Narratives

Part 1 of 3

By Mary E. Anthrop

Lafayette – Feb. 15,th 1891

“To my niece Georgie I want this book to belong after me. In it will be found many an account of old times, and settlers long passed away in Lafayette, Indiana the home of your mother and her family … that will no doubt interest you nearly as much as they do me…. All the other articles about personages I gathered as I found them and treasured for this, as such little incidents etc. in regard to same are hardly to be found in any book.”

Aunt Clara (Jenners) S. (Sweetser)

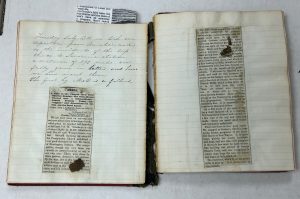

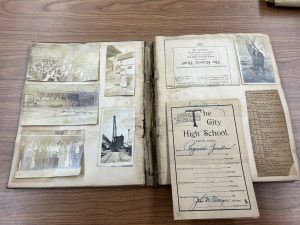

Clara Jenners Sweetser’s scrapbook is one of the many mid-19th and early 20th century scrapbooks found individually or in a collection in the Tippecanoe County Historical Association Archives (TCHA). The scrapbooks have diverse authors, representing the interests of men and women, and older and younger generations. Some creators assembled books as pastime diversions and others preserved material for professional use. Some books were for personal recollection and reflection and others, like Clara Sweetser, hoped their efforts would be read by future generations.

Today scrapbook authors journal and collect family memorabilia. They certainly might recognize the selection and organization of the following TCHA early 20th century books. Alice Ball Beemer (1878-1974) and her daughter Jeanne Beemer Dostal (1917-1972) collected clippings, such as obituaries, and souvenirs of family activities. Chauncey A. Craig’s scrapbook contained photographs, programs and ephemera on his college days at Purdue from 1911-1913. Other TCHA scrapbooks address specialized interests, like travel.

A travel album in the TCHA Archives documents one of the first transcontinental crossings by railroad. In 1869 Hon. Godlove Orth and his wife recorded their trip for newspaper readers, collected those clippings and wrote journal entries in a scrapbook. Flora Work Kern (1873-1937) kept a diary and a scrapbook of a 1905 trip to Europe. Wayne and Katherine Cory called their 1936 scrapbook of trips to the South “Our Vacation Travel Log.” Other enthusiastic scrapbook makers assembled “collections.”

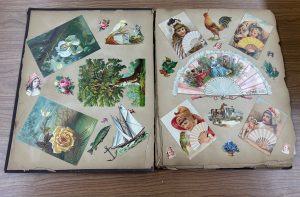

Two unidentified scrapbook makers amassed collections of chromolithograph die-cut scraps and trade (advertising) cards. Likely assembled in the 1880s both reflect artistic interests and talents. Another scrapbook of Flora Work Kern’s includes letters and signed photographs from prominent state and national figures. Author George Ade, Governor Harry G. Leslie and Presidents Warren G. Harding and Richard M. Nixon are represented in this collection. A large number of scrapbooks in the TCHA Archives reflect interests in preserving history.

A scrapbook maker interested in recording history might focus on specific national, state or local historical events or persons. Some preserve their own participation in an historical event. Reginald Zumstein in a “War Scrapbook” saved pieces of ephemeral from his travels during his World War I military training. Judge Hammond collected G.A.R. (Grand Army of the Republic) information on the 87th Regiment of the Indiana Volunteers. An anonymous scrapbook maker clipped newspaper articles and cartoons of John T. McCutcheon. Kay Dickson assembled four newspaper-clipping scrapbooks of local history. Her collecting interests were eclectic. The newspaper clippings consist of: news of religious institutions – St. Lawrence Church and School, Church of St. Mary’s and St. Joseph Orphanage; aviation history – articles on the first airmail flight “Jupiter” and Cap Aretz; and downtown street scenes of West Lafayette and Lafayette. Researchers often review the personal collections, i.e. Reginald Zumstein’s military training materials, as a primary source of information. Other collections of newspaper clippings, such as the various interpretations of the first airmail flight “Jupiter,” can be helpful as secondary sources of historical information.

A final example of a scrapbook of significant historic value is the George Durgan (four time Democratic mayor of Lafayette in the early 20th century), collection of newspaper clippings, cartoons and political ephemera. This scrapbook author records a personal and a community’s political history. A closer examination of this scrapbook can demonstrate how researchers can find both individual documents and an assembled collection itself useful in interpreting history.

The large ornate George Durgan scrapbook, 12” x 15” x 1,” contains numerous five column wide newspaper clippings. The 1904-1909 clippings represent newspapers from around Indiana – for example, Laporte, South Bend, Lafayette and Indianapolis. The scrapbook maker pasted in an original cartoon drawn by “Himan Levin.” Harold Gray, who later gained fame for his Little Orphan Annie cartoon strip, is also represented in a number of critical cartoons of Durgan.

Many newspaper articles center on reactions to Mayor Durgan’s speeches and public appearances. But other articles concern contemporary Lafayette issues. These clippings discuss: interest in an electric light plant, improvements to Columbian Park, better street car service, acquiring interurban service and a critique of the fire department. Aside from newspaper clippings in the Durgan scrapbook, the author also collected political memorabilia: an original speech with corrections, “Remarks of Welcome to the Wilder Brigade” on September 17, 1908; a program for the 12th Annual Banquet of the Jackson Club, November 18, 1907 (William Jennings Bryan was the featured guest); and a note to solicit a vote to which the recipient replied no.

A researcher finds many of Durgan’s individual documents of interest. Some of the newspaper clippings may not be readily available. The scrapbook holds one-of-a-kind original sources, such as the personal notes. The reviewer also looks at the collective sources, assembled in the scrapbook. Did the scrapbook maker create a narrative in the assembled collection?

A reviewer, looking to understand George Durgan’s political career and/or Lafayette’s early 20th century politics, likely asks questions about the author of the scrapbook and its use. Unfortunately there is no identifiable author. Did a Durgan family member assemble the scrapbook? The collection references little personal information of George Durgan or of his family. Or did a political confidant of Durgan’s, or Durgan himself, compile the scrapbook? The newspaper clippings likely would have been readily available. Some items, such as the Wilder Brigade speech, personally belonged only to Durgan. What was the intent of the scrapbook? Was the scrapbook a narrative of Durgan’s political accomplishments for history? Or did George Durgan use the scrapbook to review and reflect on his recent and future political aspirations. By deliberating such questions the reviewer hopes to discover the narrative of the scrapbook created by the author. An appreciation and understanding of the individual documents and the assembled collection assists the researcher in creating an interpretation of Durgan’s political career and Lafayette’s early 20th century politics.

A brief examination of the history of scrapbooking can help reviewers both appreciate and fully understand the meaning of the collected news clippings and ephemera in the TCHA Archives. Then a closer look at four scrapbooks, all assembled by women, will also illuminate the historical usefulness and significance of more TCHA scrapbooks.

The Scrapbook’s History

By the mid-19th century the widespread availability of daily newspapers and inexpensive periodicals seemingly overwhelmed many readers. Even a small city, like Lafayette, could boast of competing newspapers and daily, weekly, and Sunday editions. This abundance of material also seemed to disappear, as quickly as it came. Extra editions and dispatches with new material were commonplace. Afraid of losing information, many readers turned to cutting and pasting, thus preserving for later review, the best of the reading material.

The first scrapbook makers include the well known. Abraham Lincoln collected and saved conflicting views of his political speeches. Frederick Douglass encouraged the creation of scrapbooks to document African American history. Elizabeth Cady Stanton used her scrapbook clippings to help write an account of woman suffrage. Thousands of ordinary Americans created scrapbooks for professional, domestic, educational and political use. Physicians, actors, politicians, ministers, teachers, and homemakers all clipped, sorted and pasted.

Scrapbook creators of the 19th and early 20th century were often amateur historians. For the most part, they circumvented their own written words, but clipped, sorted and organized material into another original narrative. The scrapbook narrative of newspaper clippings captures a tale that would otherwise be lost or not readily found in another book. Although the author might not have been able to record their story in the traditional written word form, their novel account can reveal an authentic history and often a cultural history as well.(1)

1. For additional reading on the history of scrapbooking, particularly newspaper-clipping scrapbooks of the 19th century, see: Ellen Gruber Garvey, Writing with Scissors American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).