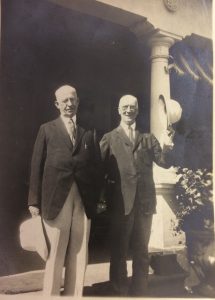

100 years ago, two Lafayette men made the trip of a lifetime. Leaving in November, 1922 and returning in June 1923, Dr. Richard B. Wetherill and Thomas Duncan traveled the length of Africa by steamer boat, canoe, train and on foot. Wetherill was a recently-retired Lafayette physician and amateur anthropologist and historian who had already traveled the world studying cultures and people. His family (on both sides), were well-known prominent local families. Wetherill had visited Egypt on his travels, but had never traveled the rest of the African continent. Duncan was a well-respect businessman and electrical engineering genius who founded Duncan Electric Meter Company. He immigrated to the US from Scotland and made frequent trips to Scotland and California. He was an avid hobby photographer, a skill he would employ on the African adventure. He had given up management of his company in 1922 and had just married his 2nd wife before leaving for Africa. So, why did they make this difficult journey? Duncan had said he had been fascinated with the Zulu tribe of Africa since he was a young boy. Wetherill, as an anthropologist and historian, had a long expressed interest in studying the people of the world. Maybe they just wanted to check an item off their bucket lists.

The Tippecanoe County Historical Association has Dr. Wetherill’s journal transcription from the trip, and Duncan’s photographs and artifacts preserved in its permanent collection. From these records, we can appreciate the trip and its impact on the local community.

In the 1920s, what did people in Tippecanoe County know about Africa? Most people likely knew at least a little about ancient Egypt. The discovery of King Tutankhamun occurred in November, 1922 and didn’t hit the media until February of 1923, so the Egypt-mania craze hadn’t struck yet. While in Egypt, Wetherill did get to visit the tomb and witness artifacts being moved to adjoining chambers. He would later give many talks around Lafayette about Egyptology and Tut’s tomb.

In 1871, David Livingstone was found in Africa (after disappearing for several years) by Henry Morton Stanley. The well-known quote “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” would have been familiar to people, as well as Stanley’s books and speaking tour about the trip to Africa.

Big game hunting was also a well-known aspect of Africa, thanks to President Theodore Roosevelt and books about hunting in African, like that written by John T. McCutcheon. The experience of hunting in Africa, however, was an opportunity only available to the wealthy and far out of reach for most residents of Tippecanoe County.

Travel at that time was done by boat or on foot. Airplane travel was still out of reach for passenger travel, even for the ocean crossing to begin and end the trip. Duncan and Wetherill’s preparation for the trip began far ahead of the voyage itself. They had to organize transportation for each leg of the trip, purchase supplies, obtain permits and practice their hunting skills. Duncan and Wetherill were not traveling to Africa to hunt “big game” as many did at that time. They did not get permits to hunt large animals, but only intended to hunt for food along the journey and for safety. Their hunting permits allowed them to carry guns and shoot all expect “royal” fauna such as elephants, giraffe and rhinos.

“I have in my life made long canoe trips on the Canadian rivers, have camped in Labrador and New Foundland, and the Hok Kaido, but this is the hardest journey I have ever undertaken with its snakes, insects, and bugs, and the intense heat, all of which is deadly, one’s life seems ever to be threatened by some insidious danger.” – Wetherill

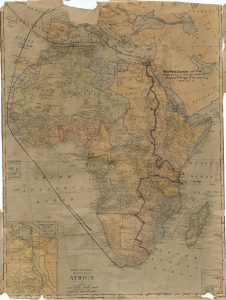

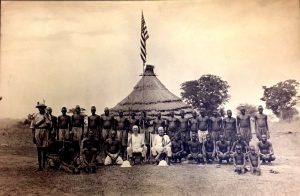

They hired a guide or dragoman named Hassan who could speak English, Arabic and Swahili. They also hired between 40 and 50 porters (throughout the trip) to carry supplies and for protection. Duncan was in charge of organizing the men, as he had experience supervising staff. They had about 30 pieces of baggage, which included mostly water and Duncan’s photography supplies. Their permits allowed them to pass through certain areas with “sleeping sickness” (a disease transmitted by the tse tse fly), but the porters could not pass through and had to be replaced at each check point. Their journey began in Egypt, then continued down the eastern coast of Africa. They ended their journey at the southern tip of the continent.

As they traveled, Duncan took many photographs of the people they encountered and their transportation. To prevent the film from being ruined by the heat, Duncan developed his film and photographs in the field, often converting their sleeping quarters into a dark room. He intended to share his images with the American Geographic Society, but it’s unclear if he ever did. Wetherill took notes on his observations; which included markets, medical practices, slavery and the general lay of the land.

Some of the highlights from their trip include witnessing the movement of artifacts from King Tutankhamun’s tomb in Egypt and visiting the site where Stanley met Livingston in 1871. They also met many Europeans and Americans who were also making similar trips and shared with them their favorite drink recipes.

Two well-known local men making an epic journey across the African continent sparked much attention in Tippecanoe County newspapers. As they sent telegraphs back home, their words were printed in the news and the community followed their path with avid interest. Upon their return, both Duncan and Wetherill gave many speaking engagements about their trip. Wetherill used this new-found popularity to give talks on many historical subjects; something he continued to do for the rest of his life. It would eventually help him gain enough interested supporters to found a local historical group- the Tippecanoe County Historical Association. Thomas Duncan died not long after the African trip, but his legacy lived on in the community center, Thomas Duncan Hall. At the time of this anniversary, some of Duncan’s African artifacts are on loan for display at Duncan Hall.

“It never pays to be in a hurry in this country, but there is a comforting sense of satisfaction in the realization that if you only keep moving, however slowly, the end of the journey will be eventually reached.” – Wetherill

Learn more about Thomas Duncan Hall