“The Blessings of Education and the Necessity of Knowledge”

Aspirations for Education by the AME Church

By guest blogger, Mary Anthrop

On April 21, 1843 a representative group from Lafayette’s small African American population met to discuss participation in an upcoming Colored People’s Convention. The Lafayette men selected a chairman, a secretary, and an assistant secretary. The assistant secretary, Samuel B. Webster, a barber, proposed an article for discussion at the September Indianapolis assembly. The gathering, which also included a visiting delegation, unanimously passed the article.

The proposal called for a plan to organize and adopt a system of common schools based upon and sustained by Indiana’s African American population. The article identified the “destitute situation” of black children in regards to “… the blessings of education and the necessity of knowledge….”(1) The men reminded parents of their obligation to educate their children and laid out an argument on the benefits of education. “It is time that we were beginning to act; time we were planting (as our white friends have done) the tree of knowledge….”(2) They claimed: “Knowledge makes the man.”(3)

While this record demonstrates Lafayette’s African American community early interest in education, more than a quarter century passed before the black community received access to a share of common school funds and admittance to public schools. Under the guidance of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, however, the Lafayette black community educated both adults and children.

Hoosier children received few benefits of public education in the years prior to the Civil War. Indiana’s first Constitution (Article 1-Section 2) in 1816 supported the creation of a general system of education. Sparsely populated counties, limited financial resources, public opposition and disinterest discouraged the building of public educational institutions. Church and private schools often filled the void left by the scarcity of public schools. In 1850 Indiana’s illiteracy rate was higher than any other northern state. An 1852 law providing for a statewide public school system contributed to initial progress, until the Indiana Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional several years later. The Lafayette City Directory in 1858 noted that the public schools opened in 1853 were closed because of the Supreme Court decision.

Black children suffered more than white children under the neglect of public education opportunities. In 1860 about 65% of white children were enrolled in a public or private school compared to less than 25% of black children enrolled in school. Popular sentiment believed that black children were unfit companions to white students. Legislation in the 1830s and 1840s denied black children admittance to public schools. Black students found educational opportunities only in church or private schools until 1869.(4)

The educational opportunities for Lafayette’s black children began in the 1840s with Sabbath School instruction in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. By 1846 the AME Church had purchased land on Cincinnati Street for a house of worship. One member of their congregation possessed the educational skills and experience necessary for teaching. Samuel B. Webster, a native of Ohio, likely wrote the Colored People’s Convention article in 1843; he was also President of the AME Sabbath School in 1844. Webster could capably read and write. In his youth Webster was a student under William H. McGuffey, who later achieved notoriety for his popular common school readers. Before coming to Lafayette Webster taught in an Infant School in Cincinnati in 1836/1837.(5) Perhaps Webster organized a Sabbath School in Lafayette for the small African American population. Webster left Lafayette sometime in late 1850 or early 1851 to colonize in Liberia.

Two records imply that the AME Church sponsored a school in 1850. The United States Census record of 1850 indicated that twenty-four of the thirty-five children aged six years to sixteen years, attended school in that year. Among the scholars were the daughter of Samuel B. Webster and the four children of Daniel Brown, the chairman of the Lafayette 1843 Colored People’s Convention. Another record, a letter in the Lafayette Daily Courier in April of 1850, praised the performance of an African American school exhibition. The writer credited Mr. Johnson, the minister-in-charge, with teaching the children, and repairing and removing the church from debt. “The rapid advancement the scholars have made during the time he has taught them has excelled any school that has ever been taught among us….”(6)

The 1860 United States Census and the Lafayette 1860-’61 City Directory identified Thomas Burgess as a schoolteacher. Burgess, a mulatto, aged 53, was born in Virginia. He resided with the Nathaniel Bannister, a cook, and his family. The 1860 U.S. Census also noted that twelve children attended school that year. Nearly nineteen children, aged six to seventeen, did not attend school. Joseph A. Russell was also listed as a schoolteacher (colored school, 84 Cincinnati, home 13th east Tippecanoe Street) in the 1864 Lafayette City Directory.

At the end of the Civil War in 1865 former slaves, many who were poor and illiterate migrated to Indiana and other northern states. Adults, as well as children, desired educational opportunities. John Fields, an ex-slave from Kentucky, came to Lafayette in 1869. In a 1937 interview he explained: “In most of us colored folks was the great desire to able to read and write. We took advantage of every opportunity to educate ourselves. The greater part of the plantation owners were very harsh if we were caught trying to learn or write. It was the law that if a white man was caught try(ing) to educate a negro slave, he was liable to prosecution entailing a fine of fifty dollars and a jail sentence.”(7) John Fields, aged 24, enrolled as a student in Lafayette’s segregated public school in the 1870s.(8)

In the spring of 1866 the growing Lafayette AME congregation considered digging a basement under their Cincinnati Street Church to construct a Sabbath and day school. The Lafayette Daily Courier, a Republican newspaper, encouraged the community to support their efforts. The newspaper reminded their readers: “It will be always borne in mind that our African citizens, although taxed for the support of common schools are cut off by the unjust and disgraceful legislation of our States from all participation in the benefits of that fund.”(9) Like most Hoosiers, however, the newspaper favored separate schools rather than the integration of black students into white schools. They feared the rise of prejudice and possible damage to public schools, if black communities pressed to enter the public school system.(10)

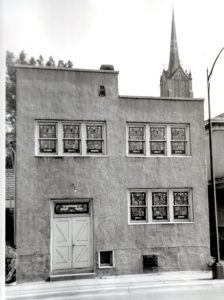

In the summer the AME congregation, however, abandoned the plan to improve their house of worship on Cincinnati Street. They purchased the church, the parsonage and the school buildings of the St. James Lutheran Church on Ferry Street. Although this purchase incurred a large debt, the congregation committed to providing religious and educational opportunities. For the next few years the congregation solicited support from other area churches. They sponsored festivals and lectures, including a public address from the civil rights leader Frederick Douglass in April of 1867, to reduce their debt. Without public support the AME Church struggled to provide academic instruction.

With the migration of former slaves to the North, national pressure mounted for state legislatures to provide educational opportunities for African Americans. In 1865 Republican Governor Oliver Morton proposed separate schools for black children. He hoped separate schools would appease public opposition to the intermingling of white and black children. The measure was defeated in 1865 and again in 1867 despite a Republican legislature. In 1869 Republican Governor Conrad Baker renewed the effort for public funded black schools. At this time the only other northern state not providing for the education of its African American citizens was Illinois. In a special session the Indiana legislature mandated that school trustees organize schools for African American children. The legislation called for separate black schools; the law also allowed communities to consolidate if a district did not have enough children for a separate school. Properties of white and black owners were to be assessed and school taxes collected on an equal basis.(11)

In September of 1869 a new chapter in African American education in Lafayette began. After completing the necessary enumeration of black children in August the Lafayette School Trustees approved the opening of a public school. The trustees, however, had no available building, and lacked the funds and time to construct a building. They accepted the offer of the AME Church to use their school building on Ferry Street. The Lafayette School trustee rented the AME School building for $13.00 a month.

The Scholarship and Deportment Book for September of 1869 listed thirty-two students. Fourteen of the scholars had attended school in 1860. Three grandchildren of Daniel Brown, the chairman of the Lafayette 1843 Black Convention, were enrolled. Two students, Lizzie Scott, a child of slavery from Kentucky, and Lucy Cox, a native of Lafayette, were almost twenty years old. Jackson Anthony, an ex-slave from Tennessee, was thirty-five. He regularly attended the public school in its first year. Sixteen of the children came from four families. Irvin Hoffman (Ervin Huffman), an Indiana native and a cook in Lafayette, sent his three children – Ellen or Helen (12 years), Gertrude (14 years) and Hiram (16 years). Hiram’s daughter, Millie Hoffman Lyda, would later teach at the black school from 1920-1949. In a 1963 letter she commented on her father’s education. “My father was a wonderful scribe, they stressed good writing, and he could WRITE. The three R’s were taught and they could READ, WRITE, and FIGURE.”(12) Eventually forty-nine students enrolled the first year. At the end of the first school year, however, only seventeen names remained on the school roster. A night school also opened to accommodate day workers.

The African or Colored School, as it was at first identified, continued at the AME site on Ferry Street until the school moved to the North-End of Lafayette. The Lafayette Daily Journal announced in July of 1880 that the School Board awarded a contract to Dan P. Wortman for $2,776. He proposed a two-story brick building measuring 27×43 feet. Wortman would build the lower story for the children and their teacher Isaac Burdine to move into by October. The Daily Journal also announced that the name suggested for the school was Lincoln.(13) While the physical presence of a school on Ferry Street disappeared, the AME Church’s interest in education did not fade. Sabbath School meetings continued and adult debate and leadership activities emerged. Messages from the pulpit promoted the education and social programs at Lincoln School until it closed in the 1950s.

[1] “Colored People’s Convention,” Tippecanoe Journal and Free Press, May 25, 1843. [2] Ibid. [3] Ibid. [4] Emma Lou Thornbrough, The Negro in Indiana before 1900, A Study of a Minority, Indiana University Press, (Bloomington and Indianapolis: 1993). See chapters 6 and 12. [5] (Letter from John G. Britton), (Columbus, Ohio) Palladium of Liberty, February 28, 1844, “Circular,” (Columbus, Ohio) Palladium of Liberty, August 28, 1844, and Report of the Second Anniversary of the Ohio Anti Slavery Society, Published by the Anti-Slavery Society, (Cincinnati: 1837). Lafayette newspaper ads and the 1850 United States Census identify Samuel B. Webster as a barber. In Liberia Webster sought a position as a schoolteacher. “Letter from S. B. Webster to Rev. J. Mitchell,” dated February 5, 1853 in Maryland Colonization Journal, August, 1853. [6] “The School for Colored Children,” Lafayette Daily Courier, April 12, 1850. [7] “Interview with Mr. John W. Fields, Ex-Slave of Civil War Period,” September 17, 1937, Library of Congress. [8] Scholarship and Deportment Book (1869-1873), Sterling R. McElwaine Collection in the Tippecanoe County Historical Association Archives. [9] “African Church and School,” Lafayette Daily Courier, March 10, 1866. [10] “The Admission of Colored Children to the Public Schools, Lafayette Daily Courier, April 10, 1866 and “Colored Children and Public Schools,” Lafayette Daily Courier, April 17, 1866. [11] Emma Lou Thornbrough, The Negro in Indiana before 1900, A Study of a Minority, Indiana University Press, (Bloomington and Indianapolis: 1993). See chapter 12. In previous years African American property had been exempt from the special school tax that paid teacher salaries. Blacks, however, were not exempt from the regular property tax accessed on both black and white properties that was used to construct school buildings. [12] Letter of Millie Hoffman Lyda to Ruth J. Anderson, November 4, 1863 in Anderson, Ruth J. Master Thesis of Science. “Negro Education in Tippecanoe County, Indiana, 1869-1886,” Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, 1964. [13] “New Colored School Building,” Lafayette Daily Journal, July 17, 1880 and “City News,” Lafayette Daily Journal, July 29, 1880.