The Artesian Well

By George Gould

Reprinted from the Weatenotes, Vol. XI, No. 6, August-September 1982

One hundred years ago the Lafayette Courthouse Square was noted for its smell – a vile, pungent, rotten-egg odor that filled the air for several block. The odor came from a fountain of artesian water located on the northeast corner of the Square. Searching for a source of pure water, the County Commissioners in 1857 contracted with an experienced well driller to dig a well. When water was struck the following February, it was free flowing but contaminated with sulphur and other chemicals. The immediate reaction was that this evil smelling but “health producing” water would be a great boon to the people of the county and could possibly make Lafayette into a new health spa.

During the next 80 years the water continued to flow, although interruptions were frequent from stones and debris in the pipe. Many local citizen made it a daily habit to take a sip from the fountain or possibly to fill a jug to take home. Finally in 1938 the flow of water stopped and the following year the Commissioners capped the well.

The idea of a free flowing or artesian well developed in the 1850’s, and after several petitions from citizens, the Commissioners let a contract in 1857 to William S. McKay, a geologist of Baltimore. The contract called for a payment of $4 a foot for the first 100 feet of drilling, $5 a foot for the second 100 feet, and $6.50 a foot beyond the 200 foot mark. In addition, if the driller struck rock, he was to receive $12 a day for his work.

McKay and his four helpers started work in April. In the beginning they had little difficulty in driving the 8” iron pipe through the first 120 feet of soil. However, on May 26 the Lafayette Daily Courier reported that the borers had encountered boulders, some as large as the pipe. From then on progress was slow with the pipe on June 16 down only five more inches. By July the depth was some six feet more. On September 7 McKay asked the Commissioners to pay the rate for drilling rock, as he had gone down only 25 feet in 89 days -–back pay of $476 was given to the crew. In December McKay asked for a contract change and shelter for his men – both requests were refused.

On February 11, 1858, the Lafayette Daily Journal reported the drill was at 216 feet when water began to fill the pipe. Regardless of a blinding snowstorm and snow 12” deep, many people came out to see the water. It had a sickening smell and tasted of sulphur. On February 19 the drill bit dropped four inches and again water surged to the top. After cleaning out the pipe and some additional drilling, water was flowing at 300 gallons an hour on March 10 and at 2,150 gallons a day on April 28. The peak flow for the well was 6,000 gallons a day in September. Experts estimated another 18,000 gallons leaked out through broken pipes and never reached the surface.

The State Geologist, a Doctor Brown of Crawfordsville, reported that soil strata of the 230 foot well as 12 of clay and gravel on top, followed by 15 feet of sand and gravel; 72 feet of marlite (blue clay); 19 feet of boulders; 29 feet of slate, and 29 feet of limestone. The underground field of water tapped by this well was said to extend to the Delphi area. Since the elevation of the water field was some 100 feet higher that the well opening, it is easy to understand the pressure and the rate of flow.

In 1858 Dr. Charles M. Wetherill, an analytical chemist, was hired to analyze the mineral content of the water. He described it as a “white sulphur water” similar to that of the famous springs in New York, Virginia and Kentucky. Elements found included “sulphurette of iron” and strong deposits of hydrogen sulphate, which gave the odor. Also found were carbonic acid, lime, magnesia, iron, sodium, calcium, hydrofluoric acid, iodine, alumina, manganese, nitric acid, sodium, chloride, and nitrogen. Doctors Brown and Wetherill agreed that the water from the Delphi field was probably pure and that the chemicals were picked up as the water passed through the limestone layer.

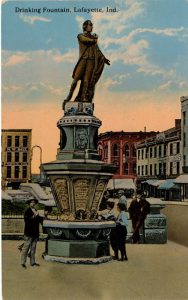

In October, 1938, it was reported that the Tippecanoe County Commissioners would award a contract to A. L. Winks for drilling of a new artesian well near the site of the original well, which had run dry. The new well would 230 feet and Winks’ bid was $600 for the work. Drilling of the new well was completed in November, but the strength of the water flow was weak enough to require a pump. A new well house was planned for construction over the new pump. Although the new well never panned out, the General de Lafayette fountain still remains on the public square, an icon for the city.