Lafayette Women Voters in the 1920s – Enthusiastic, Untried and Unfettered

“Vote as you please, but VOTE!” – Tippecanoe County League of Women Voters (1926)

By Mary E. Anthrop

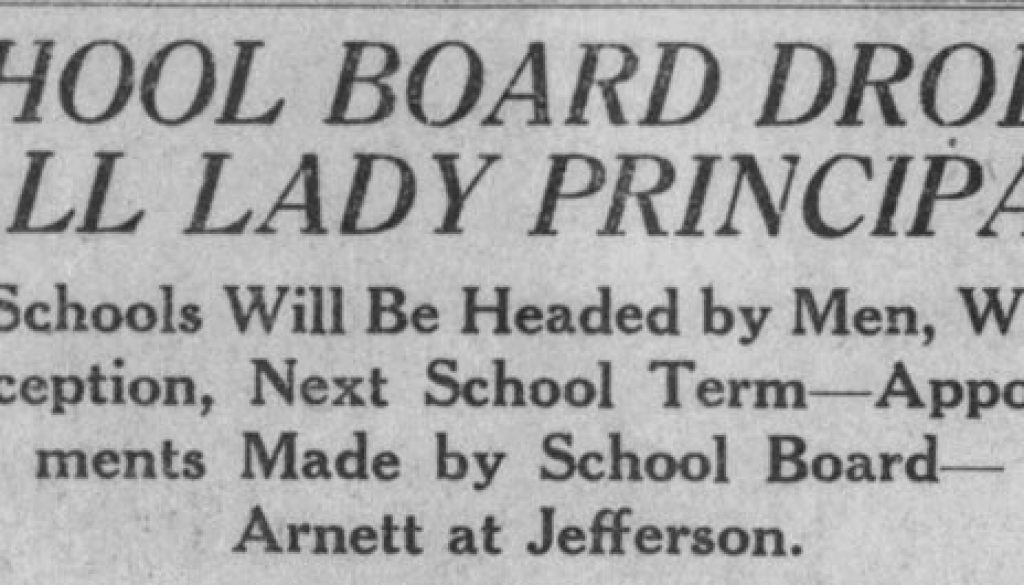

The headlines in the Lafayette Journal and Courier in mid May of 1923 shocked the citizenry. “Women School Principals May Lose Positions – Board Known to Be Considering Plan to Dismiss Them and Appoint Men In Their Place” and “School Board Drops All Lady Principals – City Schools Will Be Headed by Men, Without Exception, Next School Term.”[1] The first article identified Miss Mary Jefferson of Ford School, Miss R. Katherine Beeson of Centennial School, Mrs. Justine Taylor of Washington School, and Miss Anna C. Balkema of Columbian School, as the likely to be dismissed principals. The newly hired superintendent A.E. Highley and the school trustees defended their decision to remove the women based on the women’s lack of state qualifications for principal positions. [2] Uproar over the removal of popular and dedicated educators, three of the principals had given 119 years of service to the Lafayette community, however, gave rise to political accusations. These political accusations lingered into the 1925 city elections and helped launch a successful political campaign by Lafayette’s newly enfranchised women voters.

A citizen group organized to investigate the seemingly heartless firing.[3] Protests of sex discrimination arose from women groups throughout the city. The Tippecanoe County Federation of Clubs, representing eight clubs, the Afternoon Club, the American Association of University Women, the Business and Professional Women’s Club, and the Lafayette Art Club passed resolutions of dissent against the Lafayette school board. The Tippecanoe County League of Women Voters declared in its resolution the “… unjust discrimination against women as principals as wholly out of accord with the spirit of progress.”[4]

As the community resigned itself to the decision of the school board, the Lafayette Journal and Courier printed a stinging editorial against the Democratic Mayor George Durgan. The editorial accused Durgan of directing his appointed school board members to fire the women and replace them with men. The newspaper claimed additional evidence of Durgan’s hostility toward Lafayette’s women. At a recent Kiwanis club Durgan denounced the women clubs for their time spent passing resolutions, rather than volunteering to serve as nurses at the new visitor center at Columbian Park. The editorial concluded that Durgan’s actions were a “…slap at the womanhood of the community.”[5]

The critique of Mayor Durgan resonated with many of Lafayette’s white middle class women leaders. While both Republican and Democrat men encumbered Lafayette women’s first efforts to engage in civic participation, Mayor Durgan, a wholesale and retail piano dealer, and Democratic city councils appeared more unsympathetic. The women’s efforts in 1908 to secure an appointment of a municipal police matron failed under a Durgan and Democratic city council. A Democratic city council in 1912 and 1913 also denied petitions sponsored by the Women’s Council and Franchise League to include a woman on the Lafayette school board. The 1913 rejection, however, prompted the women to engage in more direct political action.

The Franchise League increased interest in state suffrage legislation and the Women’s Council and its auxiliary Mother’s Council concentrated on removing the Democratic city administration. They backed for mayor, Thomas Bauer, president of Lafayette Box, Board and Paper Company, and his Citizens party, a collation of Republicans and Progressives. In a close election Bauer defeated Durgan. Although Bauer readily accepted the women’s support, he did not appoint a police matron until 1915 and did not consider the women’s recommendations for the position! (George Durgan, re-elected mayor in 1918, removed the police matron position in one of his first acts).

Anticipating in 1917 that the Indiana General Assembly legislation would grant municipal suffrage, the Lafayette’s women leaders again presented a woman for the Lafayette school board. Mayor Bauer, who had returned to the Republican Party, backed the proposal, but after fifteen votes the city council deadlocked. On the fourth ballot at the next city council meeting, Serena Alder (1917-1920), widow of the prominent Republican banker William W. Alder, became the first woman to serve on the Lafayette School Board.[6] With this history of political resistance and now armed with the right to vote, would Lafayette women respond to the dismissal of women principals beyond passing resolutions of protest?

In January 1920 Lafayette woman suffrage leaders reacted enthusiastically to the news of the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution. A pioneer suffrage leader, Mrs. Mary C. Kennedy declared: “I thank God for the mothers of the world are free at last.” Serena Alder observed: “… that which the women have won after so much earnest a fight is no more than just and right.” Mrs. Henry Rosenthal’s comments, however, might have been worrisome to the established political parties. She asserted: “It is a wonderful thing that women at last have won the right to vote. I am certain that every right-thinking woman will avail herself of the privilege.”[7]

The uncertainty of how Lafayette women would exercise this new “privilege” sparked much community interest. The impact of women votes could be significant. Estimates of potential Indiana women voters was over 750,000 compared to the number of male voters in 1919 at 808,391.[8] The heavy registration enrollment in August 1920 of nearly seventy-five percent of eligible Tippecanoe County women voters and the popularity of the citizenship program offerings of the newly organized Tippecanoe County League of Women Voters forecasted a large election day turnout of women voters.

On November 2, 1920 the Lafayette Journal and Courier described women voters performing their civic duties “… with businesslike and understanding determination which was very commendable.”[9] The newspaper also noted a solemn procession of nuns and sisters from St. Elizabeth Hospital and the parochial schools marching to the polls in the early morning hours to cast their votes. Impressed by the “sacredness” of the sight, the article asserted that the occasion “…revealed a distinct departure from former days when voting was characterized by wild and disorderly scenes which served to desecrate the ballot.”[10] Anecdotal stories contradicted cynics who believed the women would vote just like their husbands and fathers. One husband was heard to remark to his wife, “Well, vote as you want to, but it will just cancel both our votes.”[11]

The first Election Day for women voters was not totally without distractions. Some registration records were lost or misplaced; a few women voters attempted to send in ballots by friends and a Republican challenger questioned a vote. An affidavit charged that Mrs. Adelaide Sherry tried to secure the vote of African American Mrs. Bessie Rollins for the Democratic ticket by giving her a dollar for her church fundraiser. The election board allowed Mrs. Sherry to vote.[12]

Women’s involvement in civic engagement expanded in 1921. Organizational and managerial skills acquired during the suffrage campaign and volunteer World War I home front activities readily transferred to the political arena. The Tippecanoe County League of Women Voters arranged and promoted their neighborhood citizenship programs. The Republican Party recruited women to assume active roles in the fall city campaign. On November 9, 1921 George Durgan was re-elected for the fifth time by a majority of 640 votes, the smallest he had ever received. The Lafayette Journal and Courier described the election: “Tuesday’s election was a hard fought contest in every ward and the strongest kind of an effort was made to get out the vote. The women worked like beavers from morning to night.”[13]

Understanding women’s place in political affairs, however, baffled political observers. The president of the National League of Women Voters, Mrs. Maud Wood Park, offered an explanation at the state convention in Lafayette in 1922. She urged co-operation between men and women voters. Men, she said, largely conduct the business affairs and are the wage earners outside the household. They have the viewpoint of business interests. Women see the affairs of government in terms of education, public health and public morals. This was the viewpoint of social welfare. Park believed that the country would be a better and happier nation when “… equal respect is given to that half of the people who know how to care for human life.”[14] This explanation might account for Lafayette’s women voters heightened interest in educational affairs.

In the year preceding the dismissal of the Lafayette women principals, controversy surrounded the operation of the Lafayette public schools. D.W. Horton (1921-1923), superintendent, addressed the League of Women Voters with his concerns in January of 1922. He criticized the low tax levy for Lafayette schools. He complained of crowded schools and the need for new additions and a new gymnasium for the high school, more playground equipment and better health services.[15] Personal antagonism with school board members, disagreements over unauthorized purchases and protests over the size of his salary led Horton to abruptly resign in December of 1922. The new superintendent, A.E. Highley, “retired” the lady principals in May of 1923.

Controversy and discord also seemed to characterize A.E. Highley’s tenure as superintendent between 1923-1932. In the fall of 1925 Highley’s unpopular handling of a strike by Jefferson High School students drew the conduct of the school administration into a dominant issue of the city election.[16] Republican mayoral candidate Dr. Albert R. Ross advocated a change in school affairs. Democrat George Durgan, in his seventh bid for re-election, was his opponent.

The Lafayette Journal and Courier on October 30, 1925 described Durgan’s control of the school trustees, as a work of disaster and demoralization. The newspaper claimed his efforts to control the operation of the schools had prevented community co-operation and impeded the city’s progressive growth. For Lafayette women voters, the appeal of correcting a social welfare issue and the disdain for an old nemesis logically drew them to Republican candidate Albert Ross. The election returns in November demonstrated their newfound political prowess.

The Republican Journal and Courier and the Tippecanoe County Democrat both acknowledged the engagement of women voters. On the day of the election the newspapers observed women involved in every way. Women were seen driving voters to the polls in automobiles decorated with “Vote for Ross” banners and purple and white streamers. Women had placed a captain on every city block and added 40 new voters to each precinct.[17]

The newspaper headlines recognized their efforts – “Republican Ticket Triumphant – Democrat Defeat Amounts to Landslide; Women Big Factor,” (Lafayette Journal and Courier, November 4, 1925) and “Democrat City Ticket is Jolted by 1043 Majority – 1245 More Voted than Four Years Ago — Women Out in Full Force to Win,” (Tippecanoe County Democrat, November 6, 1925). Party leaders credited the women for the election results. Floyd Grannon, chairman Republican City Committee, declared: “Especially do I wish to commend and give credit to the women and the wonderful organization which, thanks to the loyalty, devotion and energetic efforts of the women, made possible the election results.”[18] Mayor-elect Ross agreed: “To the women… must go the credit and glory for our victory. I don’t believe there was ever an organization like it, for effectiveness, faithfulness and hard work, in Lafayette.”[19]

The women did not see, however, an immediate reward for their political victory. While the election of Albert Ross indicated that a majority of voters advocated a change in school administration, the Democratic majority of the Lafayette School Board renewed A.E. Highley’s contract in 1927.[20] Lafayette women voters, however, had been heard and acknowledged as significant political players. No longer were women voters uncertain and untried players in the electorate. Within a few short years of winning the right to vote, Lafayette women voters activated a voice that could determine an outcome of an election. With their newfound prowess, the League of Women Voters expanded their efforts to educate women voters on citizenship responsibilities and political issues. More women joined Republican and Democratic clubs and sought political offices. By the end of the decade Mary C. Kennedy, a Democrat, won an at-large nomination for city council and in November 1929 she became the first woman to sit on the council.

[7] “Women of City Glad Suffrage Has Triumphed,” Lafayette Journal and Courier, August 18, 1920.

[8] “How Suffrage Affects State,” Lafayette Journal and Courier, August 19, 1920. [9] “County Casts Heavy Vote in the Election, Lafayette Journal and Courier, November 2, 1920. [10] Ibid. [11] Ibid. [12] “Some Find They Cannot Vote As Record Is Lost,” Lafayette Journal and Courier, November 2, 1920. [13] “Will Enter On Fifth Term First Of Year,” Lafayette Journal and Courier, November 9, 1921. [14] “The Women Voters,” Lafayette Journal and Courier, May 10, 1922. [15] “Women Voters Hear Talks On School Topics,” Lafayette Journal and Courier, January 12, 1922. [16] “School Board Shoves Highley Into Office For Another Year,” Lafayette Journal and Courier, April 11, 1927. [17] “Women Take Active Part In Contest To Determine Who Shall Govern Municipality,” Lafayette Journal and Courier, November 2, 1925 and “Democrat City Ticket is Jolted by 1043 Majority,” Tippecanoe County Democrat, November 6, 1925. [18] “ Tribute to the Workers,” Lafayette Journal and Courier, November 4, 1925. [19] “Ross Majority Is Very Large,” Lafayette Journal and Courier, November 4, 1925. [20] “School Board Shoves Highley Into Office For Another Year,” Lafayette Journal and Courier, April 11, 1927. In June of 1932 the Lafayette School Board suspended Highley for insubordination and fired him on August 27.