They “…fought as only men who have justice on their side can fight…. and did their duty to their country…. Brave men. Posterity will yet do them justice.”

Rev. J. M. Williams, April 22, 1870 in the Tippecanoe Journal

Thomas Brown (c.1825 – 1872)

In 1888 Clara Brown and her sister Eliza Brown Sweeney of Indianapolis applied for the pension funds of their father, Thomas Brown, on behalf of their younger brothers Thomas and James Brown. The sisters requested funds for the services of their father in the Civil War. The witnesses in the pension request reported the extraordinary sacrifice of Thomas Brown who served with the 28th United States Colored Troops in the Richmond, Virginia campaigns.

On his muster roll Thomas Brown claimed Vincennes, Indiana as his birthplace. He spent most of his life, however, in Lafayette where he married Martha Indicutt, formerly of Indianapolis, in 1850. Three children, Emma, Eliza and Clara were born of the union before the Civil War. A son Thomas was born in 1868 and another son James was born in 1870. To support his family Thomas Brown operated a Shaving and Hair Dressing Saloon on Main Street beginning in 1851. City directories also list butcher, whitewasher and cook as later occupations for Brown.

In late December 1863 Brown attended a recruitment meeting for African American soldiers at the African Methodist Episcopal Church on Cincinnati Street. The Emancipation Proclamation had taken effect in January 1863 that allowed the freeing of slaves in areas of rebellion. It also included a provision to allow the organization of black troops. Kansas and Massachusetts were the first free states to raise black troops. The courage and bravery of the 54th Massachusetts shown at the assault on Fort Wagner, South Carolina, encouraged the formation of additional black troops. Under the War Department General Order 143 Indiana Governor Oliver Morton authorized the organization of the 28th United States Colored Troops in late November 1863.

Local abolitionist Dr. Luther Jewett offered an additional $50 bounty for each enlistment. Brown agreed to serve and in turn recruited six others. The Lafayette Daily Courier reported on the enthusiasm of the black crowd and wrote: “The assurance that they have rights which even slave drivers may respect, and the well earned laurels of the Corps d’Afrique in the field has stimulated them with a new born patriotism….” Eventually 20 or more men from the Lafayette African American community of less than 200 citizens enlisted in the 28th USCT.

The 28th USCT trained at Camp Fremont southeast of Indianapolis and left for Washington, D. C. in late April of 1864. By the summer of 1864 the 28th USCT advanced to the outskirts of Petersburg, Virginia, a major supply center for the nearby capital of the Confederacy, Richmond. A ten-mile long defensive line of trenches and batteries protected both cities. In early June attacking Union forces advanced to within 400 feet of a well-fortified Confederate position. By this time Thomas Brown’s conduct had earned him a promotion to 2nd Sergeant and he had engaged in several skirmishes. Brown’s next experience at what became known as the “Battle of the Crater” changed his life forever.

One of the Union commanders proposed an unusual mode of attack against the Confederate’s fortified position. He suggested digging a tunnel under the fort. By blowing the tunnel up at its end it would allow Union troops to advance through the gap created by the explosion. Excavation of the nearly 600-foot tunnel took three weeks and almost another week to set up the explosives. When a fuse lite the explosives at 4:45 a.m. on July 30, 1864 the earth shook like an earthquake and then spewed red clay, men, military equipment and timber high into the air. The blast produced a crater over 170 feet long, 60 to 80 feet wide and 30 feet deep and killed or wounded nearly 300 Confederate soldiers.

After the explosion, as the Union troops advanced through the crater and the “honeycomb” lines of trenches around the crater, confusion reigned. From the advantage of a fortified position the Confederates rallied and pounded the advancing troops with canisters and mortars. The battle continued into the mid afternoon; Confederate troops forced the Union soldiers into retreat. The black troops suffered the most casualties with the 28th USCT losing nearly one-half of their numbers.

The Lafayette Daily Courier reported on August 12 that six men of the 28th USCT from Lafayette died at Petersburg and nine men were wounded. Thomas Brown left no personal details of his role in the battle. The 1888 pension affidavits, from fellow soldiers, however, testified that Brown made a charge upon Crater Hill and was “…exposed to the deafening explosions and noises of battle and heavy cannonading from 5 a.m. to 11 a.m.” Furthermore the black veterans described the impact of the battle on Thomas Brown.

Veterans who knew Brown from Lafayette swore to his robust health and sound mind at the time of his enlistment. They believed that he suffered a concussion during the battle and never again seem to be in his right mind. They also claimed his physical health also deteriorated; he became morose and irritable, even hallucinating at times. While Brown was well liked by all of the men of the regiment before the battle, he never was the same person in words or actions. A modern diagnosis of Thomas Brown’s state of mind after the Battle of the Crater likely would be shell shock, combat fatigue or post traumatic stress disorder.

Military records do not reveal any acknowledgement or treatment for Brown’s instability after the battle. On November 8, 1865 the Union Army mustered Brown out of service from Corpus Christi, Texas. He then returned to his family in Lafayette. Perhaps the local black community, however, recognized his service. In April of 1870 they chose Brown as one of the parade marshals for a celebration of the passage of the 15th Amendment in Lafayette. The festivities included a march of local and Indianapolis dignitaries, proclamation reading, and speeches by Rev. J.M. Williams of Indianapolis and Governor Baker. A festival at the AME Church on Ferry Street concluded the celebration.

Sadness soon found the Brown family. In March of 1872 Martha Brown died. In May the Indiana Home for the Insane in Indianapolis admitted Thomas Brown with a diagnosis of mania. The doctors believed Brown to be homicidal and his insanity due to the bereavement on the recent death of his wife. No one noted on his admission record his service in the Civil War. Janeral Tootle, a long-time friend, however, claimed in a pension affidavit that Brown came out of the army in 1865 “…laboring with a trouble in his head…. and “… he finally gradually growing worse, was sent to the Indiana Asylum for the Insane where he died.”

Thomas Brown passed on December 1, 1872. The authorities at the Indiana Hospital for the Insane expected no one to claim his body and subsequently buried him on the grounds of the asylum. Tragically his Civil War sacrifice was ignored and forgotten.

For additional reading see: Mary E. Anthrop, “‘Posterity will yet do them Justice,’ Thomas Brown’s Call to Military Duty in the Civil War,” Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History 25 (2013); George P. and Shirley E. Clark, “Heroes Carved in Ebony: Indiana’s Black Civil War Regiment, the 28th USCT,” Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History 7 (1995); Alan Axelrod, The Horrid Pit: The Battle of the Crater: The Civil War’s Cruelest Mission, Carroll and Graf Publishers, 2007; and Eric T. Dean, Jr., Shook over Hell: Post-Traumatic Stress, Vietnam and the Civil War, Howard University Press, 1997.

“By education we can better our position.”

Sterling R. McElwaine on the opening of Lincoln School, 1923

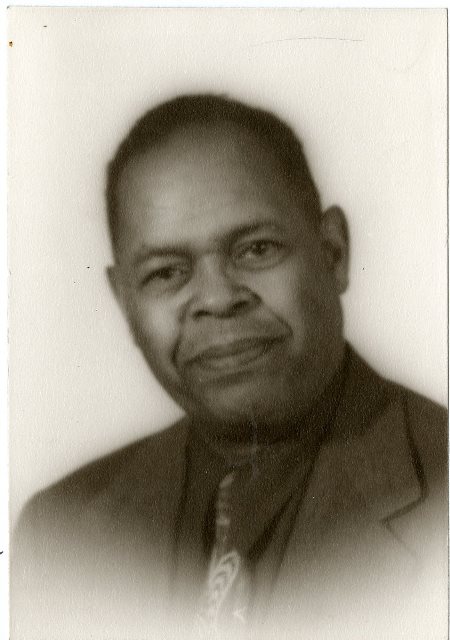

Sterling R. McElwaine (1887-1971)

For over 50 years Sterling R. McElwaine served the Lafayette community as an educator in the Lafayette School system. He was a teacher and principal and book rental director, but McElwaine’s public service also extended into the larger community. In 1965 he received a Journal and Courier George Award for outstanding leadership ability and community service. McElwaine’s service to the Lafayette community began in 1909 when he became the principal of Lincoln School in the North-End of Lafayette.

In 1963 notes in the TCHA Archives McElwaine described the early challenges he faced. He noted that black elementary children lived throughout the city and all attended Lincoln School despite the severe winter weathers and the long distances to walk. When the student population grew from 47 pupils in 1910 to over 90 in 1915, the old two-classroom school was overcrowded; he needed to upgrade the facilities and hire another teacher. His biggest task was boosting confidence in the benefits of education. “They (students) would say ‘What’s the use,’ I don’t need a high school education to wash dishes, clean house, or other menial labor’.” From 1895 to 1912 only two Lincoln students graduated from high school.

By 1916 McElwaine organized a Parent-Teachers’ Club (PTA) at Lincoln School. (Later the Lafayette PTA Council acknowledged his leadership and awarded McElwaine and his wife life memberships in the state PTA group). Two portable classrooms were added to Lincoln School; one classroom was used for Manual Training and Domestic Science and the other for classroom instruction. By the early 1920s the black pastors representing the Lincoln community pressured the city for a larger and more modern facility. In 1923 a new $54,000 brick Lincoln School opened on 14th and Salem Streets with classrooms, gymnasium and an assembly hall. The school also served as a community center. At the dedication ceremony McElwaine said: “By education we can better our condition.” He noted that enrollment in Jefferson High School increased to 22 black students by 1923 and noted that a black scholar headed the school’s honor roll. During his tenure (1909-1949) as principal of Lincoln School 117 Lincoln students graduated from Jefferson High School and 29 graduated from college. The Lincoln graduates included nurses, medical technicians, pharmacists, teachers, community center directors, a policeman, a dietician, and a social service worker.

McElwaine’s encouraged the Lincoln School neighborhood to take an active role in Lafayette’s community activities. Lincoln School graduates were listed on the Jefferson High School honor roll. Despite their small enrollment numbers Lincoln students successfully competed in city track meets and basketball tournaments. In 1929 Lincoln children won a citywide school contest to purchase an elephant for the Columbian Park Zoo. When Lafayette clubs and organizations sponsored school fundraisers and benefits, the Lincoln School community organized a miscellaneous program of readings and musical selections by the children. (Mrs. Ethel McElwaine, an expert candy maker, made and sold her candy. The Altrusa Club, a sponsor for Lincoln School, bought over 30 pounds)! Lincoln School won the right to name the elephant. The children chose the name – Lincoln.

Sterling R. McElwaine left Lincoln School when it closed in 1949 and the children integrated into the public grammar schools of Lafayette; he retired from the Lafayette School System in 1961 after serving more than 10 years as book rental director. In his educational career McElwaine served as the vice president of the Lafayette Classroom Teachers Association, president of the Lafayette Principals Club, and served for more than 20 years as clerk of the Lafayette Employees Federal Credit Union.

As a member of the Second Baptist Church, he served as clerk, treasurer, chairmen of the trustee board, Sunday school teacher, choir member and treasurer of the Parsonage Club. He was also a member of the Human Relations Council, Indiana School Men’s Club, board of directors of the Red Cross and of the Society for Crippled Children and Adults; he chaired the 1964 Easter Seal campaign.

In 1921 Sterling R. McElwaine married Ethel Naomi White. She died six months before his death, October 26 of 1984. Surviving his death were his two children, Sterling Jr., and a daughter Mrs. Robert Small both then living in Chicago.

Reference: See Sterling R. McElwaine Collection in the Tippecanoe County Historical Association Archives