Daniel Brown (1796-1881)

“…we shall still remember him as a Christian believer who was always full of sweetness and light.”

Rev. Robert McDaniel, March 24, 1881 in the Christian Recorder

In Joseph Yundt’s Account Book (1836-1838) in the Tippecanoe County Historical Association Archives, Yundt noted purchases of candles, shoes, starch, and sugar by the sexton of St. John’s Episcopal Church, Daniel Brown. He also recorded barber William Findley’s purchases of boots, coffee, broad cloth and muslin. Yundt’s notation of “(colored)” by the names of Brown and Findley confirm the presence and the economic activity of African Americans in a pioneer community.

Both Brown and Findley played significant roles in the early history of the African American community in Lafayette. William Findley migrated to Liberia in 1850, but Brown lived in Lafayette for over 40 years. (Brown resided for several years at the Fort Wayne home of his son John. Brown died in Fort Wayne on February 25, 1881). According to the 1840 census Daniel Brown, his wife and six children were among the five African American families living in Lafayette. Later censuses identify his date of birth, 1796, and his birthplace, Maryland. Censuses also list his occupations as white washer, laborer and sexton at St. John’s Episcopal Church. A spokesman for the African American community in an 1881 Lafayette Weekly Journal article called Daniel Brown “a pioneer of the colored people in Lafayette.” Brown’s reputation and legacy rested on his religious and moral leadership.

In the History of Saint John’s Church, Jane C. Harvey reported that older members of the church remembered Brown with “great pleasure and interest.” They recalled a faithful, earnest Christian who gave many years of efficient service to the church. Brown and his wife Melissa were communicants of St. John’s and confidents of Reverend Samuel R. Johnson, the first rector of St. John’s.Reverend Johnson, an abolitionist from New York, said that in times of disheartenment he found strength and hope in their strong faith. In 1837 Johnson performed the first marriage of St. John’s – Sarah Ann Brown (perhaps Daniel Brown’s daughter) to William Findley.

Brown embraced religion in 1821 and Bishop Payne ordained him a Deacon at an African Methodist Episcopal Church conference in Terre Haute sometime in the 1840s. In 1843 the Tippecanoe Journal reported that Brown chaired Lafayette’s Colored People’s Convention. The delegates called for a state meeting in Indianapolis and approved a resolution to promote the education and moral improvement of black children in Indiana. In 1846 Brown, as one of the trustees of the newly formed African Methodist Episcopal Church in Lafayette, solicited funds to purchase land for a church building. He continued as a trustee of the AME Church well into the 1860s. In 1866 his name appeared on deed records as a trustee for the purchase of new church property on Ferry Street, the current location of the AME Church. At the AME Church in 1870 Rev. Daniel Brown participated in the preparations for a celebration of the passage of the 15th Amendment – the extension of suffrage to African American men.

In the Christian Recorder on March 24, 1881, Rev. Robert McDaniel of Fort Wayne, who visited Brown in his last days, acknowledged his religious service to the Lafayette community. “He had literally laid down and gave up his life in the service of the church. About two months before he died a school teacher said to me who was from Lafayette, Ind., where Brother Brown had lived so long, ‘if he could come back to Lafayette, his old home, and the people get to know it, the church could not hold the people who would come to see and hear him.’ But when we forget all these things we shall still remember him as a Christian believer who was always full of sweetness and light.”

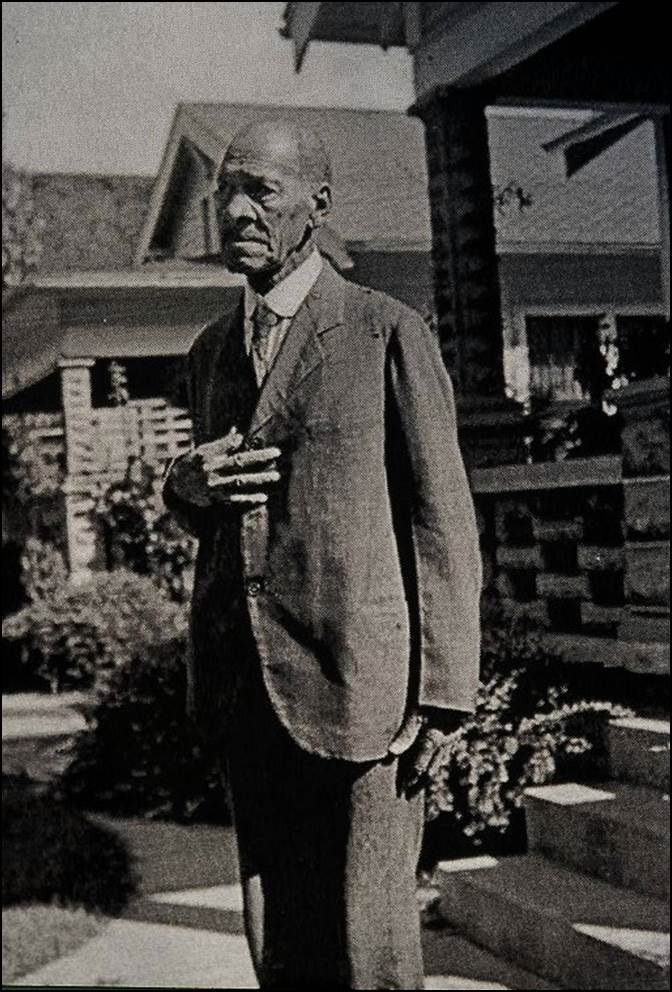

John M. Fields (1848-1953)

“Our ignorance was the greatest hold the South had on us.”

Interview with John M. Fields, ex-slave from Kentucky, September 17, 1937

During the Great Depression, Cecil Miller, of the Work Projects Administration (WPA), interviewed a familiar figure of the North-End community in Lafayette, John M. Fields. Miller’s assignment was to record the narratives of elderly former slaves for the Library of Congress. Fields, of North 20th Street, had resided in Lafayette since 1869 having fled from the slave state of Kentucky during the Civil War. Fields’ recollections evoke the brutalities of slavery and the resilience of the African American spirit.

In the 1937 interview Fields identified his birthplace as a plantation in Owensburg, Kentucky. At the age of six, the master of the plantation died. Fields and his 11 siblings were taken from their parents to settle the estate. Fields never saw his mother again for more than a day at a time. Fields further described his life on a tobacco plantation with his new mistress: “…my life as a slave was a repetition of hard work, poor quarters and board. We had no beds at that time, we just ‘bunked’ on the floor. I had one blanket and manys the night I sat by the fireplace during the long cold nights in the winter.” He also witnessed the harsh treatment towards other slaves. “I remember one incident that I don’t like to remember. One of the women slaves had been very sick and she was unable to work just as fast as he thought she ought to. He had driven her all day with no results. That night after completing our work he called us all together. He made me hold a light, while he whipped her and then made one of the slaves pour salt water on her bleeding back. My innerds turn yet at that sight.”

Fields depicted his time in slavery as “… filled with heart-aches and despairs.” One of the slaves great desires was to learn to read and write. “We took advantage of every opportunity to educate ourselves. The greater part of the plantation owners were very harsh if we were caught trying to learn or write. It was the law that if a white man was caught try(ing) to educate a negro slave, he was liable to prosecution entailing a fine of fifty dollars and a jail sentence. We were never allowed to go to town and it was not until after I ran away that I knew that they sold anything but slaves, tobacco and wiskey. Our ignorance was the greatest hold the South had on us.” (As a young man in Lafayette, John Fields’ name appears as a regular scholar in the records of the black school).

At the start of the Civil War Fields believed at first that the South would win the war, “… as most of the big battles were won by the South.” According to Fields, his master kept the news of emancipation from the slaves, as Kentucky had not seceded from the Union and planters from other southern states sent their slaves to Kentucky. Fields did not act on his freedom until 1864. Then Fields and his brother ran away and tried to join the Union army. The Union army accepted his brother, but turned him away as being too young at 16 and too small at 112 pounds. Fields eventually found work in Indianapolis as a general laborer at $7 a month.

Fields held a variety of jobs during his life of 104 years. He spent two years in Benton County clearing land for the town of Fowler; for three years he drove the carriage of W. S. Lingle, then editor of the Lafayette Courier; he whitewashed houses; and Fields worked as a janitor for the Underwood Insurance agency for 20 years. In 1872 Fields married Elizabeth Scott, a former slave and native of Georgetown, Kentucky. They had four children; Elizabeth died in 1927. Together they acquired three properties in Lafayette.

Fields’ obituary in 1953 remembered him as a community minded citizen and a deeply devout religious leader. Local fire fighters honored him on various occasions and dubbed him the dean of Lafayette auxiliary firemen. In 1872 he became one of the 12 charter members of the Second Baptist Church and was baptized in the abandoned Wabash and Erie Canal at the foot of Salem Street. He often recalled his baptism as one of the highlights of his life. A foot of ice had to be cut away before the ceremony and ice clung to his clothing afterwards. Fields noted: “I didn’t even catch cold.” In the early days of the Baptist Church organization Fields collected donations and subscriptions for building the church on Hartford and Salem Streets. He also drove a wagon to the outskirts of town to collect rocks for the building’s foundation. After he became a lay preacher in 1874, he would preach one Sunday to raise money to pay for the expenses of the next Sunday’s scheduled minister. He served for over 70 years, even preaching on his 100 birthday in 1948.

To read more of John Fields 1937 interview see the collection: Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936 to 1938 at: https://www.loc.gov/collections/slave-narratives-from-the-federal-writers-project-1936-to-1938/about this collection/