150th Anniversary of the Passage of the 15th Amendment

By guest blogger, Mary Anthrop

“The event to be celebrated is one of the most memorable in the world’s history. It is no light thing to lift into the body politic four million people heretofore as a class, robbed of the products of their labor, and stripped of their personal liberty.”

It was a diverse gathering at the African Methodist Episcopal Church on Ferry Street in Lafayette. Nathaniel Bannister and Henry Schultz were over sixty years of age; Daniel Brown was over seventy. Thornton Crenshaw and Russell McDonald were much younger men, by almost forty years. Some of the men could neither read nor write. Most of the men were laborers; but several were cooks and barbers. Bannister, a cook, had acquired property worth $1000 and Wilson Giles, a barber, owned property valued at $2000. Daniel Brown was a sexton for the first minister of St. John’s Episcopal Church in the 1830s and his son, Thomas Brown, a Civil War veteran, was born in Lafayette. Others claimed Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and Mississippi as their place of birth; they came to Lafayette as emancipated slaves. The men, however, shared an optimistic view of a near future with full political equality and they united in their enthusiasm for a long anticipated celebration of the granting of suffrage.

Passed by Congress in 1869 and ratified by the states in February of 1870, the 15th Amendment granted the right to vote to African Americans men. “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color or previous condition of servitude.” National Republican support of the amendment stemmed from a desire to protect black voting rights and Republican state governments in the South. In a narrow contest for ratification by the states Senator Oliver Morton of Indiana, a former governor, successfully introduced legislation that required four southern states to include the ratification of the 15th Amendment as a condition of their re-admission into the Union. The 15th Amendment’s immediate benefactors were northern men, like the Lafayette black men, as only eight northern states at the time of ratification allowed African Americans to vote.

The actions of Tippecanoe County Republicans encouraged the optimism for equal political participation among Lafayette’s black population. In early February Tippecanoe County Republicans convened to select delegates to the Republican State Convention later in the month. By unanimous vote the gathering supported the resolution by Joseph Odell, an attorney, “… the male colored citizens of Tippecanoe County, twenty one years of age and over, have a right to participate in the action of this convention upon equal terms with its white members.”[1] The Lafayette Daily Journal endorsed this action. “The black man is an American citizen, clothed with all the rights, privileges and immunities that belong to the proudest and humblest alike in this now redeemed land … it is his duty, as well as privilege, to be represented in political conventions and State and municipal legislatures.”[2] (Eventually the Republican State Convention selected a black Vice-President and several delegates were African American; no black representatives from Tippecanoe County attended the convention). Furthermore a February 10, 1870 Daily Journal editorial also declared: “The colored voters have a right to express their choice at the primary election (in April)… There will be no intimidation at a Republican precinct when the colored citizens come up to illustrate the Declaration of Independence.”[3]

On March 3, 1870 the black men, assembled at the AME Church, quickly organized a committee to make arrangements for a celebration of the ratification of the 15th Amendment. Next came a series of resolutions. Rev. H. Coleman introduced a resolution of gratitude to “… those who advocated equal rights before the law without regard to race or color.”[4] Other resolutions acknowledged the persuasive efforts of Senator Morton and of the Republican Party in securing the passage of the 15th Amendment. Finally the men pledged their unanimous support of the Republican Party at the ballot box. On April 5, 1870 the Lafayette Daily Journal reported that Irvin Huffman, Indiana born, employed as a city janitor, cast the first black vote in the Republican primary. The newspaper estimated about thirty other African American men voted. (There were approximately forty-two black eligible voters in the city).

Throughout March and early April the AME Church congregation continued discussions on arrangements for a celebration. They voted down the idea of celebrating with the people of Indianapolis. The Committee of Arrangements decided on an April 21 celebration consisting of a procession, a day meeting with speeches and a festival at the AME Church at night. They invited Rev. J. N. Williams of Indianapolis to give the main address. Local participants included: Rev. Daniel Brown to preside on the day of the celebration; Rev. S. Alexander to act as chaplain and Rev. W.H. Coleman to read the proclamation. All Lafayette friends were invited to participate in the festivities.

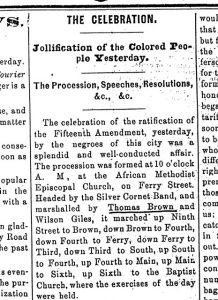

The Daily Journal described the celebration on April 21 as a ”splendid and well-conducted affair.”[5] The Daily Courier said the festivities “…reflected very creditable on our colored people.”[6] The procession led by the Silver Cornet Band and marshaled by Thomas Brown and Wilson Giles began at 10 o’clock at the AME Church. Nearly one hundred marchers made their way throughout downtown Lafayette. Some carried declarations: “Union and Liberty Forever,” “We will Stand by Our Friends,” “We will Educate our Children,” “We will Stand by the Right,” “We Cherish the Memory of Abraham Lincoln,” and “200,000 Colored Volunteers Send Greeting.” When the procession arrived at the Baptist Church on Sixth Street the exercises began.

Rev. S. Alexander offered a prayer to open the celebration and Rev. Coleman read the proclamation of President Grant announcing the ratification of the 15th Amendment. The Rev. J. M. Williams of Indianapolis, a former slave who had purchased his freedom in 1851, was then introduced to give the main address.

The Rev. J. M. Williams of Indianapolis spoke to the crowd in an hour-long extemporaneous speech. Williams did not believe that the celebration was for his race alone. “… (I) prefer to call the Fifteenth Amendment the nation’s freedom, and all colors and all nationalities share in the results….”[7] He proceeded to trace the history of the nation’s debate over slavery from the inception of the principles of the Declaration of Independence, to abolitionist efforts, to recent Congressional actions over reuniting the states. The Civil War, was the turning point. It was not only a white man’s war. Black men fought “… as only men who have justice on their side can fight.”[8] He believed the Fifteenth Amendment was the joyous result of a well-fought battle. “No American citizen may now be ashamed of his country. No black spot stains our country’s flag, and it is now indeed the land of the free and the home of the brave.”[9] He concluded his address with advice to his fellow black citizens. “Go slow but ask for all your rights as a citizen. Do not let others think for you. … Educate your young, learn trades, buy your homes… shun saloons and gambling places, read solid books… and thus be ready for any emergency, so that when victory complete is the country’s boon, you may be among those whose highest boast shall be that he was an American citizen. America with no North, no South, but proud free America.”[10]

After Rev. Williams’ address, Governor Baker, who was in the city to attend to business connected with the Agricultural College (Purdue), and Colonel W.C. Wilson of Lafayette gave short and fervent speeches. Both men offered advice to their impressionable audience.

Next Rev. Coleman proposed nine resolutions, which echoed the sentiments of Rev. Williams. The assembled passed them unanimously. He noted that the black citizens of Tippecanoe County recognized the 15th Amendment as ”… the final triumph of right over wrong; of justice over injustice, oppression and prejudice….”[11] The 15th Amendment fulfilled the principles of the Declaration of Independence and inspires the African American population to avail themselves of opportunities of education and industry in order to live peaceful, moral and religious lives. Coleman remembered those who stood by the black man in the dark days of slavery, and identified President Grant as a friend of his race. Finally the gathering pledged support of the Republican Party as long as it “…remains true to its grand principles of right….”[12]

The last remarks of the day in the Baptist Church included the reading of a celebratory letter from Congressman Godlove S. Orth. A musical selection followed and the assembly broke up. The ladies of the AME Church planned for the festivities to extend into the evening with a supper. Open to all for ten cents admission the event successfully raised $60.00 for the minister’s salary.

With the day’s activities concluded, Lafayette’s black community likely agreed to the Daily Journal’s evaluation of the celebration. “There will, doubtless, be unthinking people, today who will deride the pageant that is to appear on our streets, and there will be others who will seize upon the occasion to fan into fierceness the wicked flame of prejudice (Lafayette newspapers recorded an attack by white boys against a black coachman at the end of the celebratory supper festivities); but no right-minded person will fail to applaud the efforts the colored people will make to show how fully they appreciate the magnitude of the blessings conferred upon them by the nation.”[13] Despite the continuing challenges of racial prejudice and discrimination into the 20th century, Lafayette’s small black community heeded the advice of Rev. Williams and Rev. Coleman. The men voted and organized Republican clubs. Community members bought homes, opened businesses and formed lodges. Black families formed a second religious congregation, the Second Baptist Church, and supported education for their children at Lincoln School. Truly members of Lafayette’s black community could claim the highest boast of being American citizens.

For additional reading see: Emma Lou Thornbrough, The Negro in Indiana Before 1900, A Study of a Minority, First Indiana University Press Edition 1993

[1] “Republican County Convention,” Lafayette Daily Journal, February 7, 1870

[2] “The State Convention,” Lafayette Daily Journal, February 19, 1870 [3] Editorial, Lafayette Daily Journal, February 10, 1870[4] “Meeting of Colored Citizens – Proposed Celebration of the Ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment,” Lafayette Daily Journal, March 3, 1870

[5] “The Celebration,” Lafayette Daily Journal, April 22, 1870 [6] “The Fifteenth Amendment Celebration Today,” Lafayette Daily Courier, April 21, 1870 [7] “The Celebration, “ Lafayette Daily Journal, April 22, 1870[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid. [10] Ibid. [11] Ibid. [12] Ibid. [13] “The Celebration To-Day,” Lafayette Daily Journal, April 21, 1870