Clipping, Collecting and Pasting: Assembling Scrapbook Narratives

Part 3 of 3

By Mary Anthrop, guest blogger

2 more scrapbooks from the TCHA archives.

Helen Mar Jackson Gougar Scrapbooks

More than twenty-five years after the scrapbooking efforts of Rebecca Gordon Ball, Helen Mar Jackson Gougar (1843-1907) assembled at least two scrapbooks. Gougar, however, embraced a more public persona than Rebecca Gordon Ball. Her scrapbook clipping and pasting pursuits likely reveal both a desire to record her historical role in reform movements and an effort to create a practical tool for use in her public career.

Helen Mar Jackson, a native of rural Hillsdale County, Michigan, joined a brother and three uncles living in Lafayette in 1860. At the age of sixteen she began a teaching career in the recently re-opened public schools. The Lafayette school trustees awarded her a principal position before her 1863 marriage to lawyer John Gougar (1836-1925) of Ohio. John Gougar suffered from poor eye sight, at times being confined to his home, and Helen obtained considerable knowledge of the law by reading to and researching for him. The Gougars had no children.(1)

The Lafayette Courier reported on a three-day woman’s suffrage convention in Lafayette in November of 1869. While there is no documented evidence of Helen Gougar’s attendance or participation in this gathering, about this time she began a public life. By the spring of 1870 Lafayette newspapers noted her involvement in the activities of the Second Presbyterian Church, the YMCA, the Lafayette Home Association and the Ladies Benevolent Society. In the next two decades Gougar began a newspaper career, as a journalist and editor, and emerged as an out-spoken and uncompromising temperance and woman suffrage reformer. In her thirty-year public career she gained state and national attention and influence. By the turn of the century, Helen reduced her public appearances and Helen and John devoted more time to world travelling. Helen Gougar died unexpectedly of heart failure on June 6, 1907.

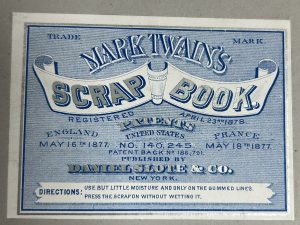

Helen Mar Jackson Gougar’s two scrapbooks contain columns of newspaper clippings from 1879-1880 and 1880-1893. Gougar pasted her newspaper columns “Bric-A-Brac Literature, Science, Art and Topics of the Day” (1879-1880) from the Lafayette Courier into a large and partially used “Our Herald” (a newspaper Gougar edited and later owned between 1881-1885) account book. In a smaller red and black decorative Mark Twain Scrapbook(2) Gougar preserved newspaper clippings dated 1880-1893. These clippings came from newspapers of various cities in Indiana: Fort Wayne, Indianapolis, Kendallville, Lafayette, and Plymouth. She also saved newspaper scraps from Rockford and Joliet, Illinois and Attleboro, Massachusetts.

Helen Gougar’s “Bric-A-Brac” column debuted in the Lafayette Courier in November of 1878 and she wrote nearly one hundred columns between November 1878 and September 1880. The first scrapbook clipping pasted in the account book, however, is dated November 22, 1879. The thirty columns in the scrapbook run continuously until July 31, 1880. Obviously the “Bric-A-Brac” newspaper clippings are not complete. The reviewer might ask: did Gougar organize an earlier scrapbook and perhaps create a later one? The reviewer can only speculate on its incompleteness. Perhaps her emerging activities as a lecturer limited the time she could devote to clipping, sorting and pasting scraps.

If Helen Gougar pasted the clippings in a dated (1882) Our Herald account book, was the scrapbook assembled several years after the appearance of the columns in the Lafayette Courier? A reviewer can find only one handwritten comment by Gougar in the scrapbook. In a space before a lengthy editorial column the note reads like a later correction: “The poem and head (headline) belonging here will be found pasted in one of my European travel books. H. M. G.” This scrapbook contains only a third of Gougar’s earliest newspaper writings, but did Gougar create this scrapbook to preserve the history of her early journalist career?

Helen Gougar did not document her activity, as an editor of the columns. A reviewer of the scrapbook may find answers in the content and organization of the newspaper columns. Most of the “Bric-A-Brac” columns were eclectic, consisting of poems and stories by her sister Edna Jackson, commentaries on the human condition by various authors and local community “scraps” and social news. Gougar’s editorials sometimes adopt religious arguments; she comments on the efforts of local charitable organizations and she expresses concern for the care of the insane. Gougar also reveals her interests in education, likely drawing on her experiences as an educator, in several columns. These first efforts follow traditional ideas of domestic reforms. This newspaper clippings scrapbook also discloses her developing interest in social issues and emerging demands for political action.

In several editorial columns, May 22, 1880 and July 17, 1880, Helen Gougar addresses the importance of the education of children, particularly girls. Gougar believes “…mental food is as essential to the existence of a child as bodily food….” (3) In “The Girls of a Household,” she stresses the importance of teaching self-reliance to girls. “We plead for self-reliance, we plead for respect, we plead for liberty on the part of our girls.”(4) Girls need book-learning and instruction in practical ideas of everyday life or they risk becoming dependent helpless women.

Helen Gougar’s most passionate editorials discuss the plights of widows and their children and liquor restrictions at the annual County Fair. The January 17, 1880 editorial, “A Day Among the Poor of the City,” reads like an investigative reporter’s expose. Gougar describes a day with Fairfield trustee M.H. Gallagher on a routine round of visits with widows and their children. She empathizes with the plight of the widows, including their conversations in the editorial, but she also sympathizes with the trustee’s challenges of distinguishing between the “worthy and unworthy poor” of over 100 families (including 300 children). She describes the circumstances of the poor: “No money, no wealthy or influential relatives or friends, no homes, no credit, the ‘grim wolf of want;’ is their constant companion.” She declares that the poor “are nor morally depraved, but are poverty depraved” and she implores the women of the Lafayette churches to help their own sex.(5)

Another editorial, “Shall Intoxicating Liquors be Sold at the County Fair?” in the July 24, 1880 column, takes an even more ardent demand for action. Temperance groups emerged in Lafayette in the late 1870s. At first they labored with “prayers and tears” and “pleading voices” to encourage drunkards to abandon intoxicating liquors and to deter young men from adopting intemperate habits. Gougar’s editorial identifies the beginnings of more widespread influence of the temperance groups. Gougar challenges the Directors of the County Fair to deny the sale of intoxicating liquors at the fair. If the Directors allowed the sale of liquor it “… would be a decisive step backwards and would exert a might influence for evil.”(6) The protesting temperance advocates successfully promoted a boycott of the county fair while liquor was sold; no county fairs were held in 1883 and 1884. The county fair re-opened in September of 1885 and did not allow the sale of beer from tents.

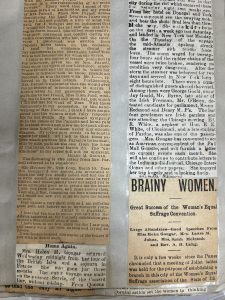

The “Bric-A-Brac” column scrapbook preserves for history the early journalistic career of Helen Gougar, likely Lafayette’s first woman journalist. Gougar, however, perhaps saw a different purpose for her second scrapbook. The smaller scrapbook, dated 1880-1893, is a varied collection of thirty-two local, state, and national newspaper clippings. The collection does not appear to be a comprehensive record of Gougar’s activities between 1880 and 1893. There are notable omissions. There are no clippings relative to the Our Herald, the newspaper owned and edited by Gougar between 1881 and 1885 or to the infamous Gougar-Mandler scandal trial (1882-1883). Did Gougar simply not have the time, because of her active public career, to assemble a thorough newspaper clipping collection?

Certainly Helen Gougar’s preservation of her public appearances and political clashes may simply indicate a desire to historically record her voice in the suffrage and temperance movements. Helen Gougar’s “1880-1893” scrapbook contains clippings of her arguments for extending the rights of women: the “Welcoming Address” (June 16, 1880) of the Lafayette woman suffrage convention in 1880 and “The Law and the Ladies How Can the Civil and Political Rights of Indiana Women Be Enlarged Without Constitutional Amendment,” in the Indianapolis Journal of January 6, 1885. The clipping, “The Campaign of 1888,” (November 6, 1888) an address on behalf of the Prohibition Party at the Lafayette Opera House, was the longest preserved newspaper report – thirty-five columns. Most, if not all, of the newspaper articles, however, also lend themselves to an analysis of the effectiveness of Helen Gougar as a political reformer.

Helen Gougar may have also assembled the seemingly diverse newspaper clippings for a professional review of her political activities. Women reformers emerged as more frequent public speakers in the 1880s and became increasingly conscious of their representation in newspapers. They recognized the influence of the press to promote, but also to ridicule or denounce suffrage and temperance reforms. Reformers reviewed not only the critiques of speeches, but also the comments on the delivery and the composure and appearance of the orators. They also believed that the reports of social appearances, conventions, and even “feuds” between opposing reform factions were helpful in understanding public responses to their reform activity. For reformers the analysis of newspaper clippings provided strategies for future undertakings.(7)

As a newspaper columnist and editor of the Our Herald, Gougar likely recognized the influence the press in converting the public to suffrage and temperance reforms and the acceptance of women as politicians. Notably many of the articles chronicle Gougar’s emerging participation within the Prohibition Party. Gougar wrote and saved “The Life and Work of the Great Orator,” a biographical sketch of John P. St. John, a Prohibitionist governor of Kansas. She clipped the “War on the Wabash,” a Lafayette newspaper article. John G. Williams, the editor of the Lafayette Sunday Times, insinuated that a WCTU (Women Christian Temperance Union) meeting had been held in a “questionable place” – Helen Gougar’s home. After a sidewalk confrontation, Gougar offered $100 to anyone who would “whip” Williams. Gougar also pasted reactions to her debates with Anna Dickinson, a post-Civil War activist, and her feud with Hoosier suffrage leader May Wright Sewall. Both rivalries originated from differences over prohibition activity.

Helen Gougar’s activity in temperance and the Prohibition Party movement obviously generated controversy. She faced both opposition and ridicule from the “liquor interests” and even fellow reformers. (Many leading woman suffrage leaders thought that embracing the Prohibition Party distracted from the main objective of achieving the right to vote). Frequent or even periodic review of newspaper commentaries would help Gougar evaluate the success of her appearances and provide strategies for future endeavors.

In the middle of the scrapbook Helen Gougar pasted an undated and unidentified newspaper clipping on “Female Politicians.” In a lengthy article Gougar rebutted James G. Blaine’s, a onetime presidential candidate in 1884, displeasure with “female politicians.” He objected to women in the political field, “…for the reason that they are unfitted for that kind of work, not only mentally but physically. They have not the training and they can’t get and retain their womanliness. Mentally they are unable to hold a body of politicians, and physically they haven’t the voice or the oratorical power of speech.” Gougar argued: “…the brain of a smart woman is quite as capable of deciding her proper sphere as the brain of a smart man is of deciding his proper sphere.”(8) She then proceeded to attack his arguments against women politicians with examples from the careers of accomplished woman suffrage and temperance reformers. In conclusion she described her own successful oratorical campaigns and challenged Blaine to a talking match.

Almost all of the preserved articles reference both the effectiveness of Gougar’s presentations, as well as the reasoning of her arguments. Many of the clippings are complimentary. In the clipping, “Rats, Says Mrs. Gougar,” the reporter commended Helen Gougar delivery on the right of suffrage. “Mrs. Gougar physical energy and crowding rush of ‘talk’ is something marvelous. It is doubtful if her equal can be found among all the other women on the American platform today.” In “Ananias’s Big Sister” (July 9, 1893), an account of the rivalry with May Wright Sewall, a reporter noted: “ She is a most attractive and witching personality, of fine and handsome face and physique and has a full musical voice of ample oratorical modulation, and, in sparkling, style of rhetoric, and method of treatment of her subject, Mrs. Gougar stands preeminent as the rostrum-speaker of the age.”(9)Helen Gougar did not save only the flattering commentaries on her appearances.

While the author of an unidentified newspaper clipping expressed sympathy for a scathing review of a Helen Gougar’s temperance address in Logansport, Gougar cut and pasted “Two Views” in the middle of her scrapbook. The article in part read: “The speech… was the tirade of a gifted public scold and reckless partisan…. Her brazen repetition of exploded falsehoods; her pitiful tricks for the deception of unwary groundlings; her miserable misrepresentations of the best men and women in the country; her railing and mouthing conspired to beget disgust among all whose good opinion is worth having.”(10)

Unfortunately Helen Gougar did not write any descriptive notations in the scrapbooks. She occasionally identified the source or date of the newspaper clipping. Notations might have provided the definitive evidence of how Gougar intended to use the scrapbooks. Some might argue that the reviewer is left to only speculate on Gougar’s narratives. Recognizing how contemporary woman reformers used scrapbooks, however, might suggest that Gougar created an historical record of her suffrage and temperance activity and a practical reviewable political handbook.

Clara Jenners Butler Sweetser Scrapbook

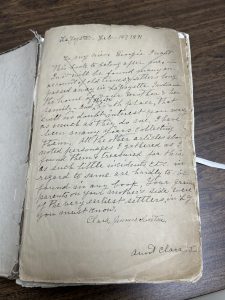

At the age of 53 Clara Jenners Butler Sweetser (1838-1925) assembled a large scrapbook, three newspaper clippings wide, in an old account book. An avid newspaper clipper for years, Sweetser described the narrative of her scrapbook in a foreword to her niece Georgia, Georgianna Jenners Jones Hiller (1884-1950). On February 15, 1891 Clara Sweetser wrote:

“To my niece Georgie I want this book to belong after me. In it will be found many an account of old times, and settlers long passed away in Lafayette, Indiana the home of your mother and her family … that will no doubt interest you nearly as much as they do me…. All the other articles about personages I gathered as I found them and treasured for this, as such little incidents etc. in regard to same are hardly to be found in any book.”

Clara Sweetser concluded her preface with a reminder to her niece that her grandparents on her mother’s side were some of the earliest settlers in Lafayette.

Clara Jenners was born January 2, 1838 in a log cabin on the corner of 3rd and Ferry Streets. Her parents, David and Maria Simpson, had settled in Lafayette in 1828. Clara’s siblings included: Deborah, Sarah, and Lavenia, Georgia’s mother. Clara Jenners married twice, but the unions did not bare children. She married George Butler (1830-1878) in 1864 and William Sweetser (1830-1900) in 1881. Clara was the last surviving member of her family when she died in 1925.(11)

Clara Sweetser’s newspaper clippings scrapbook has a straightforward narrative. She hoped to provide Georgie, her niece, with a history of Lafayette, Indiana. (Georgia, at the time her aunt began the scrapbook’s compilation in 1891, was only seven years old and living in Alabama. She later moved to Lafayette). Sweetser accomplished her objective by cutting, collecting and pasting hundreds of Lafayette obituaries and newspaper clippings of local historic interest. She also inserted occasional personal notations on the history of the Lafayette community. Finally, Sweetser peppered the scrapbook with miscellaneous scraps – poems, essays and feature stories.

Clara Sweetser assembled a collection that dates from the 1880s into the early 1900s and reflects the historical period when the oldest of Tippecanoe County’s pioneer settlers were passing. The obituaries and newspaper clippings in themselves provide modern researchers access to Tippecanoe County primary sources that may not be readily available. Her selection of newspaper clippings also records her perspective on the events and people she considered being of historical significance. This scrapbook narrative helps the reviewer understand a turn of the century historical view of Tippecanoe County. Sweetser revered the pioneers for their struggles and sacrifices in establishing a home in the Indiana wilderness. She was undoubtedly proud of her family’s connections to the past history of Tippecanoe County.

Clara Sweetser did not collect contemporary news articles for historic preservation. There are no clippings, for example, of the current Lafayette politics, business development, or social movements. Sweetser’s historical narrative centers on the biographical record of Lafayette’s pioneer founders and their achievements.

In the mixture of male and female newspaper obituaries, the number of male obituaries clearly outnumbers the female obituaries. Notable female obituaries include, Edna Ruby, an artist, Mary A. Williamson, an art embroidery designer, and Helen M. Gougar, a suffrage and temperance reformer. The male obituaries frequently follow a formula that highlights business, political and military activity. Sometimes Sweetser wrote personal notes identifying a family connection to the deceased. She selected few minorities for her collection. The obituary of Sarah Clark, a 106-year-old African American woman, is an exception. She also included two articles on Irish immigrant Nancy Tigue (husband Patrick). The newspaper clippings acknowledge the 105th and 106th birthdays of Tigue, who lived in Lafayette for over 60 years.

Clara Sweetser collected newspaper features that recalled the settlement history of Lafayette and Tippecanoe County. Histories of Fort Ouiatenon and the Battle of Tippecanoe are represented in her collection. One of the longest articles that Sweetser saved was the ten-column article on the dedication of the Battle Ground monument. The article paid tribute to the struggles and sacrifice of the soldiers who died in the Battle of Tippecanoe. Sweetser preserved articles that recorded the history of the first taverns and tavern keepers in Lafayette, the earliest theatrical performances and the cholera scare of 1849. She saved columns titled “Scraps from Memory’s Note Book,” “Lafayette’s Old Men” and “Fortune Favors Them” an article identifying Tippecanoe County men who paid taxes on over $10,000.

Clara Sweetser personally connected to the historical events and people. She wrote a lengthy explanation of why she saved a recollection of the 1856 execution of convicted murderers on the courthouse square. One of their victims was the family’s neighbor. She saved articles that extolled the contributions of St. John’s Episcopal Church and First Baptist Church. She noted that as she pasted the newspaper article on the First Baptist Church on January 22, 1891 she recalled that her mother was the oldest living member of the congregation. On the newspaper article that featured the likeness and biographies of Lafayette’s Civil War officers she wrote individual notes on the accuracy of their images In one particular article on the life of Abraham Lincoln Sweetser remarked that the Lincoln likeness was how she recalled him when she attended Lincoln’s funeral in Springfield in 1865. Her reverence for President Lincoln was obvious. In one of the numerous articles about Lincoln she underlined a concluding remark: “…Lincoln, with all his foibles, is the greatest character since Christ.” She added, “I believe it, dear old Abe.”

Clara Sweetser also showed a preference for other national stories of American heroes. She included stories on John Paul Jones, George Washington, and Presidents of the United States. The sheer number of articles on the Civil War perhaps testifies to her thoughts on its significance in her lifetime and of its influence in the 19th century. She clipped and preserved articles on Harriet Beecher Stowe, John Brown’s Raid, Camp Morton in Indianapolis, the passing of General Lew Wallace, the origins of Wilder’s Brigade, an escape from Libby Prison, the final days of the Confederacy and a Soldiers Home in Ohio.

Finally Clara Sweetser inserted assorted articles of personal interest. In addition to the occasional romantic or sentimental poem, she selected newspaper feature articles. Sweetser found discussions of Queen Victoria and the English aristocracy – “very interesting” and she enjoyed stories of “prima donnas,” Emma Abbott, Litta and Adelina Patti – contemporary singers. Sweetser pasted a four column wide article on “Professional Beauties,” a story about popular faces known for their beauty and a two-column article on “Baltimore Beauties.” Interestingly she noted on the article “First Ladies of the Land” that she hoped that the Presidential wives “were all much better looking” than the printed images suggested!

Clara Jenners Sweetser wanted her scrapbook revisited by her niece, and perhaps by other generations. The reviewer might speculate that Sweetser would have been pleased that the scrapbook eventually landed in the archives of the Tippecanoe County Historical Association. A photocopy of the scrapbook’s pages and a list of the obituaries in the scrapbook are readily available to researchers

1. For a biography of Helen Gougar see Robert C. Kriebel, Where the Saints Have Trod, (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 1985).

2. The “Mark Twain’s Self-Pasting Scrap-Book,” available by 1877, featured horizontal gummed strips in two or more columns. The scrapbooks varied in sizes and styles. Prices for the scrapbooks ranged between forty cents and five dollars. The scrapbooks eliminated the messy glue pots, but did restrict the layouts of the clippings. As the name “Mark Twain” appeared prominently in the scrapbook ads, Samuel Clemens profited from the sale of his novel invention. The revenues of the scrapbooks even surpassed the sales of his popular written publications.

3. “Children’s Reading,” Lafayette Daily Courier, July 17, 1880.

4. “The Girls of a Household, Lafayette Daily Courier, May 22, 1880.

5. “A Day Among the Poor of the City,” Lafayette Daily Courier, January 17, 1880.

6. “ Shall Intoxicating Liquors Be Sold At The County Fair?” Lafayette Daily Courier, July 24, 1880.

7. Ellen Gruber Garvey, Writing with Scissors American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), chapter 5. For a discussion of the role scrapbooks and the press played in the woman suffrage and temperance movements see chapter 5, Strategic Scrapbooks: Activist Women’s Clipping and Self-Creation.

8. “Female Politicians,” undated and untitled newspaper, 1880-1893 Helen Gougar Scrapbook, in Helen Gougar Archival Collection.

9. “Ananias’s Big Sister,” Washington Chronicle, July 9, 1893, 1880-1893 Helen Gougar Scrapbook, in Helen Gougar Archival Collection.

10. “Two Views,” undated and untitled newspaper, 1880-1893 Helen Gougar Scrapbook, in Helen Gougar Archival Collection.

11. “Pioneer Woman, Last of Family, Dies in Hospital,” Lafayette Journal and Courier, May 11, 1925.