Second Baptist Church

A Cultural Contribution from Southern Freedmen

By guest blogger, Mary Anthrop

“I didn’t even catch cold….”

John Fields describing his baptism in the old canal at the foot of Salem Street in the 1870s

Lafayette Journal and Courier, March 27, 1941

When recently emancipated enslaved people after the Civil War arrived in Tippecanoe County they faced political, economic and social challenges. In the 1870’s the freedmen cooperated with the established black residents to celebrate the passage of the 15th Amendment, form Republican political parties, and support the first public school for blacks, Lincoln School. With limited resources the southern natives, who came mainly from Kentucky and Tennessee, also organized a new religious congregation in the Second Baptist Church.[1] By the end of its first decade the Second Baptist Church had become a significant center of African American life in Lafayette.

A Lafayette Daily Courier article on February 3, 1872 announced the formation of the Second Baptist Church the evening before. The Rev. R. W. Pearson of the First Baptist Church had allowed a group of twelve or so to the occasional free use of the church’s lecture room on Sixth Street. They also desired the services of a black preacher. The Rev. Moses Broyles, for many years pastor of the Second Baptist Church in Indianapolis and known historically for organizing many Baptist churches in Indiana, preached that night. The evening concluded with the organization of a black Baptist church. Some of the charter members included Jackson and Mary Anthony, originally from Tennessee and Virginia, Jordon Scott and his daughter Elizabeth from Kentucky, Cornelius Fletcher from Virginia, Katherine Wheeler from Tennessee, and John Fields from Kentucky.

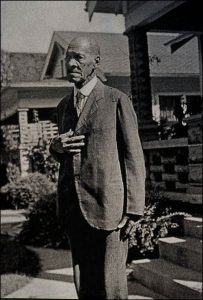

John Fields held the honor of being the first person baptized after the formation of the congregation. In 1869 at the age of twenty-one Fields had moved to Lafayette from Kentucky. [2] John Fields fondly recalled his baptism experience in a 1941 newspaper interview. A foot of ice had to be cut from the old canal at the foot of Salem Street and ice clung to his clothing afterwards. He said: “I didn’t catch cold, you didn’t catch colds in those days.”[3]

Others baptisms occurred at the foot of Salem Street in the 1870’s. One Lafayette Journal (March 24, 1879) account of a baptismal service described the shameful and disorderly conduct of white observers. The report condemned the behavior and noted how the reverend “…took no notice of the ribald jests of the ‘smarties’ who sought to disturb him in his solemn duties.”[4]

A 1950’s History of the Second Baptist Church (found in the TCHA library vertical file) described the first challenging years of the congregation. The charter members selected their first pastor, Rev. William Neal, and two deacons, Jackson Anthony and Jordan Scott. Rev. Neal preached every other Sunday for $5.00, a sum that was a large amount for the small group. In the first years there were times when no minister could be secured or enough money to pay his expenses. Jordon Scott always housed the minister and furnished him all of his meals. Luckily John Fields, after his baptism, was licensed to preach in 1874. He continued to serve his church past his 100th birthday.

The small band of Christian devotees struggled the first winters to gain conversions, but they persevered. Jordan Scott, no matter how challenging the weather conditions, collected his fellow worshipers in his two-horse wagon to haul them to their meeting place. Even if the regular meeting place could not be obtained, worship took place in a member’s home. Some members of the Lafayette’s white community took notice of their pious efforts. The ensuing white cooperation encouraged the growth and stability of the Second Baptist Church.

John Levering, a Civil War veteran and a leader in the First Baptist Church, offered his help in building a permanent meeting place. He proposed that each man belonging to the church should contribute thirty-five dollars and encouraged Jordan Scott, Thornton Granshaw and John Fields to solicit donations and subscriptions for building supplies. Levering promised to donate a lot at Sixteenth and Hartford Streets and twenty thousand bricks. To ensure a solid foundation for the church that would keep the walls from sagging and cracking, Levering also proposed building a rock base three feet deep and twelve inches wide. Joseph Huffman and John Fields then took to gathering rocks for miles around in Jordan Scott’s two-horse wagon. They secured rocks from creek beds, fields, along roadways, and from cooperative landowners. By 1877 the congregation built the Second Baptist Church at the cost of thirty-one hundred dollars.

Having a permanent place for worship allowed the Second Baptist congregation more opportunities to foster learning and fellowship among its members and the larger Lafayette community. William H. Levering, a relative of John Levering and a member of the white Baptist Church, organized the Sunday or Sabbath School and was superintendent of it for nineteen years. The societal African American news columns in the Lafayette Journal for 1879 frequently reported attendance of 30-40 Sunday scholars. A Christmas celebration at the Second Baptist Church in 1879 also caught the attention of the Lafayette Journal. In observance of a then novel idea of distributing gifts from a Christmas tree a reporter complimented the black Baptist congregation on their efforts. “We found the folks had put their little church in good shape, and while the tree was not as large as some that grow in California it bore good fruit for the little folks. The presents were nice, and were distributed in a most equitable manner and reflected great credit upon those who managed the affair.”[5]

Both white and black Lafayette churches often sponsored public suppers and ice cream or strawberry festivals. Funds raised help to maintain and improve church facilities, pay minister expenses, or support Sabbath School and mission activities. A Lafayette Journal newspaper note on September 27, 1879 reported on the utilization of funds secured from a successful Second Baptist festival. “The new Baptist Church has been plastered, and is now a very cozy little place of worship, and the congregation are to be congratulated upon the zeal with which they have worked to get their church complete.”[6] These public festivals also encouraged interactions between the white and black communities allowing for possible cultural exchanges.

The Baptist congregation organized by the new Southern migrants, enjoyed, and perhaps introduced to Lafayette, the cakewalk (originally an enslaved person dance mimicking flamboyant southern plantation owners) at its festivals. John Fields, one of the original charter members, was one of the popular dancers.[7] An October 11, 1879 note from the Lafayette Journal described one of the successful events. “The festival at the Second Baptist Church, Wednesday evening, was a success. It was largely attended, and a very enjoyable time was had. There was a dialogue that brought down the house. There were several trials of speed, grace and endurance in predestrianism for cakes, &c. There were several cakes awarded…. The proceeds were about thirty dollars, to apply upon the payment for the street improvement near the church, which will be a desirable part of the city when finished.”[8]

With limited resources, but with fervent resolve, the Southern freedmen of the Second Baptist Church had established a stable foundation in less than a decade from their formation. The Second Baptist Church had built a permanent meeting place for worship, education and fellowship. By early 1880 the cohesiveness of the congregation was vital to the success of the small black community in Lafayette. The Lafayette Journal predicted a hopeful future: “The outlook for the colored people of this city seems good…. Our colored people are well represented in our churches (the Methodist and Baptist). Also our Sunday schools and day schools are in a very healthy condition…. Societies are being organized which will have a tendency to draw those who hitherto spent their time in saloons and gambling halls to more profitable places and more honorable pursuits. With industry and economy we may yet be an honor to society and a blessing to the community in which we live.” [9]

__________________________________________________________________

[1] With the migration of Southern freedmen after the Civil War into Indiana the black Baptist churches experienced explosive growth. According to L.C. Rudolph’s Hoosier Faiths A History of Indiana Churches and Religious Groups (page 585), the Baptist churches had many attractive characteristics. “A Baptist church could begin anywhere with a minimum of outside authorization or regulation. Male members could proceed to ‘be somebody’ at once if their leadership was welcomed by their peers. ‘Mothers’ and ‘Sisters’ could also hold honored places. Lack of formal education did not disqualify. The informal services, the heartfelt manner of evangelism, the dramatic baptisms, the democratic decision process in which any member could speak and all members vote, the absence of white domination – all these had great appeal.”

[2] When John Fields was six he was separated from his parents and siblings and sent to another tobacco plantation. Fields learned of the Emancipation Proclamation, but not until 1864, and then he resolved to run away and join the Union Army. Rejected by the Union Army as being too young for service, he removed to Evansville, Terre Haute and then Indianapolis. He worked as a laborer and finally settled in Lafayette. Although he was an adult, Fields attended the first publicly funded black school in Lafayette, Lincoln, to learn to read and write. See the 1937 John Fields interview at the Library of Congress – Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936 to 1938.

Visit the Library of Congress Website CLICK HERE

[3] “John Fields, Born a Southern Slave, Is Active at 93,” Lafayette Journal and Courier, March 27, 1941.

[4] “Baptismal Service,” Lafayette Daily Journal, March 24, 1879.

[5] “At the Colored Baptist,” Lafayette Daily Journal, December 25, 1879.

[6] “The Colored People,” Lafayette Daily Journal, September 27, 1879.

[7] “Our Colored People,” Lafayette Daily Journal, April 26, 1879. [8] “ The Colored People – A Few Words About Them, Collected by One of Them for the Journal,” Lafayette Daily Journal, October 11, 1879. [9] Ibid.