“What Hath God Wrought?”

By John M. Harris

Editor’s Note: This article first appeared in the Tippecanoe County Historical Association Newsletter “Weatenotes” Vol. VIII, No. 2 for May 1974.

His name was Morse, Samuel Finley Breeze Morse, painter of portraits and sometime dabbler in electronics.

He was tall, thin and 52 years of age with sandy colored hair well on the way to being grey. He was also greatly depressed. Slowly he sipped his coffee and picked at his breakfast. Sadly he mulled over the events of the past two weeks and the struggle by him and his friends to get a bill through Congress, which would prove once and for all the value of his invention. The bill would appropriate $30,000 “to test the practicability of establishing a system of electromagnetic telegraphs by the U.S.” The bill had squeaked through the House by a vote of 89 to 83 and had gone to the Senate with only eight days remaining before Congress would adjourn. Although there were 140 other bills ahead of his on the Senate docket, he had clung tenaciously to the hope that somehow he would be successful. Yesterday had been the final day of the session, and he had stayed in the Senate Gallery late into the evening, long after the lamps, which illuminated the chambers had been lit.

Realizing finally that it was hopeless to think that they would ever get to his bill, Morse had given up in despair and returned to his hotel room. His personal money was almost entirely gone. His dream had been shattered. Once breakfast was over he must make arrangements to return home to New York.

“Sir”, the servant’s voice interrupted his unhappy thoughts, “there is a young lady waiting in the parlor to speak with you.”

Although not exactly relishing the prospect of having company, he was pleased to see that it was young Annie Ellsworth, the 16-year-old daughter of his friend Henry L. Ellsworth, the Commissioner of Patents. Morse and Ellsworth had been good friends since their college days together at Yale, and Henry had been an important ally in the struggle to obtain government support for Morse’s telegraph.

Hastening toward him, Annie said, “I have come to congratulate you.” “Indeed, for what?” “On the passage of your bill.” “Oh, no, my young friend, you are mistaken. I was in the Senate Chamber quite late last evening and my Senatorial friends assured me there was no chance for me.” “But, she replied gleefully, it is you who are mistaken! Father was there at the adjournment at midnight and saw President Tyler put his name to your bill. Am I first to tell you?”

Could it be true? Yes, it must be! Annie would never play such a cruel joke. The news was so unexpected that for a few moments he could not speak. Finally, he replied, “Yes, Annie, you are the first to inform me. And now I am going to make a promise. The first dispatch on the completed line from Washington to Baltimore shall be yours.”

“I shall hold you to that promise,” she said, smiling as she turned to leave.

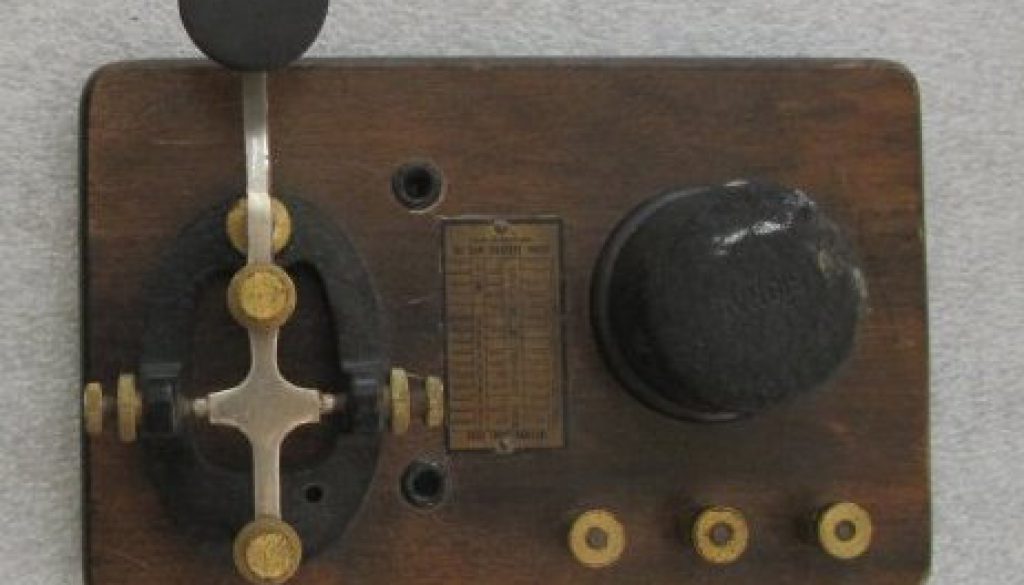

And thus it was that on the morning of May 24, 1844, only slightly more than a year later Annie Ellsworth happened to be present in the Supreme Court Chambers to help make history. Near the center of the courtroom, which was then located in the Capitol Building, sat a strange-looking object–Morse’s telegraph. She knew that this instrument was connected by wires to an identical instrument in the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad station in Baltimore – over 40 miles away!

Clustered around the table in Washington were her friend Mr. Morse and a number of other dignified individuals, some smiling and obviously friendly; others just as obviously skeptical. With a stir of excitement, Annie recognized Henry Clay, who had recently launched his campaign for the presidency and nearby Dolly Madison, wife of James Madison, the fourth president of the United States.

The group hushed as Morse seated himself at the table and quietly asked Annie what the first message was to be. She handed him a slip of paper on which was written a passage from the Bible suggested by her mother: What hath God wrought?” (Numbers 23:23). Quickly Morse sent the words using the dot and dash code, which bears his name. It was received in Baltimore and repeated back. As the words were de-coded in Washington, the room erupted with cheers. The age of electronic communications had been born! Other inventions were to follow rapidly—the telephone, the teletype, the wireless radio, television, and more. But few if any people in the room that morning realized how important electronic communication would become in the future. When Morse later offered to sell his telegraph to the government for $100,000, it was rejected as being merely a scientific toy that would never be self-supporting.

What happened to Annie Ellsworth, the young girl in this drama? Her older brother, Henry E. Ellsworth, had moved west to Lafayette, Indiana, in about 1837. Like many later arrivals, Henry E. became enthusiastic about the potential of the area and launched a campaign to persuade Easterners to buy land here. Among those so persuaded was Annie’s father who moved his family here from Washington in 1845, one year after the historic event described above.

A family home was built on the northwest corner of South and Seventh streets. (In later years this structure was enlarged and was known as the Stockton House.) In a short time, Ellsworth and his son were among the largest landowners in the area, owning literally thousands of acres in Tippecanoe, Benton, Warren and Newton counties in Indiana and in Illinois.

Back East, Ellsworth had known a brilliant young law student whom he persuaded to come to Lafayette to assist with the management of the vast Ellsworth landholdings. This young man was Roswell C. Smith who lived in the Ellsworth home as a member of the household. In time, a romance developed between Annie and Roswell and they were married on July 5, 1851.

Almost immediately, Smith left for the East to finish his education, earning his law degree from Brown University in 1852. This accomplished, he returned to Lafayette to practice law.

Roswell and Annie moved into a spacious home known as “Cedar Cottage” on the northwest corner of Seventh and Columbia streets. Later, this was the site of the Columbia Apartments. Here they lived until 1870 at which time the Smiths moved to New York where Roswell took up the magazine publishing career that would make him nationally famous in the publishing world. In the years that followed he founded St. Nicholas, Scribner’s and Century magazines. He also became a benefactor of Berea College in Kentucky. After suffering several months of ill health, Roswell died on April 19, 1892, at the age of 63.

Annie and Roswell became the parents of two daughters, one of who, Julia, married the famous American painter George Inness, Jr. Annie gained a reputation as a cultured and warm individual who entertained many of the literary celebrities of the time in her home, including Edward Eggleston, author of The Hoosier Schoolmaster and Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. On January 21, 1900, Annie Ellsworth Smith passed away at the age of 73.

As a sidelight to this story, during World War II it was necessary for the telegraph companies to hire girls to fill the positions formerly held by messenger boys. Eventually, the question was raised as to who was the first messenger girl. As is often wont to happen with matters of such importance, a small controversy developed. Then in May of 1944, the U.S. government issued a 3¢ commemorative stamp honoring the centennial of Morse’s invention. The research done prior to the issuance of this stamp proved that Annie had not only composed the first message, she had also delivered it (to Morse in the court chamber). Thus Annie Ellsworth was the first telegraph messenger girl, thus ending the controversy.