His Death Started a Bloody War by Quentin Robinson, County Historian

B Franklin Tolby appeared on the census with his family in 1850 but after that his name appears as James Frankin Tolby or Franklin J Tolby. The name change is not explained in any family documents or biographical material.

Soon after 1850 Thomas Tolby settled in Tippecanoe County, north and west of Battle Ground in Tippecanoe Township. By 1860 J. Franklin Tolby is teaching school in Tippecanoe Township while the rest of his brothers were engaged in farming.

On the 6th of August 1862 James F Tolby enlisted at Lafayette into company G of the 72nd Indiana Infantry Regiment for service in the Civil War. He was discharged 26 June 1865. The Regiment served as mounted infantry during most of 1863 and 1864. They served in campaigns throughout the south including the capture of Chattanooga, the Battle of Chickamauga, Kennesaw Mountain, Siege of Atlanta and many other operations throughout the south. One of their last operations was the pursuit of Jefferson Davis at the end of the war.

By the time the 1870 Census was taken Tolby had married earlier that year to Mary Russell and had purchased a small farm west of Brookston. As fate would have it, farming apparently did not suit Franklin J Tolby.

He had joined the Methodist Church during a camp meeting near Battle Ground in 1857 and what he wanted to do was to become a preacher. In 1871 he was admitted on trial to the Methodist ministry and thereafter served churches in White, Benton and Newton Counties. In 1874 Tolby volunteered and was sent as a missionary to New Mexico where he was stationed at Cimarron but also served the Methodists in Elizabethtown which at the time had become a gold mining boom town.

Based on the recollections of those who knew him, Frank Tolby was personable and well regarded in the communities he served. He was described as bold and fearless both in the pulpit and out and was a naturally talented and compelling speaker.

Reverend Tolby, his wife Mary and their two young daughters, Rachel and Grace, had arrived in Cimarron at a particularly troubled time. You might say he landed right in the middle of a nest of mad hornets. Trouble had been brewing for a couple of years but there had not been any violence, at least not the kind that resulted in death.

In the 1850’s, Lucien Maxwell, a son-in-law of Beaubien, took on the active management of the land grant and after Beaubien’s death in 1864 Maxwell and his wife bought out the other heirs at a cost of about $36,000. Under Maxwell’s management settlers had arrived, but they were mostly Americans. Maxwell did not have formal arrangements with most of those who settled on his land, he was running several businesses that profited off the settlers in other ways and that made collecting rents less important. In 1870, Maxwell sold the grant to financiers representing British investors for the sum of $1,375,000 and afterwards retired comfortably to Fort Sumner, New Mexico where he died in 1875.

If the families refused to vacate, threats of violence were used and in some cases buildings, pastures or crops were burned, and livestock either driven off or killed. There was widespread belief that the Grant owners and managers had paid off judges and other officials so that every legal challenge the settlers made was defeated. There were accusations of corruption, many of which were later proven to be true.

There was a strong feeling among the Americans who had settled on the grant that the land should be converted to public domain land and put on the market by the Federal Government. They believed that the original grant had not complied with Mexican Law and should be vacated or at least sized down by about half. Others argued that any grants that had been made by Mexico should be null and void simply because the United States had won the Mexican war.

It did not take Reverend Tolby long to take sides and he was firmly on the side of the settlers against the Foreign owned land company and the local politicians (known as the Santa Fe Ring) who enabled the bully tactics being used by the company. Tolby not only preached against the company and their enablers from the pulpit in both Cimarron and Elizabethtown, but he soon started writing long detailed letters describing the situation to newspapers back east. One of his “editorials” published in the New York Sun in which he named names associated the group known as the Santa Fe Ring and described their corrupt political methods. That one apparently caught the attention of the wrong folks in New Mexico.

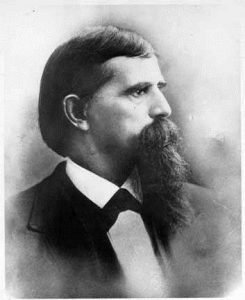

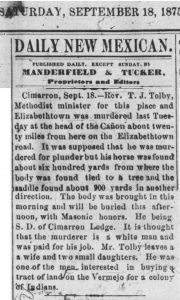

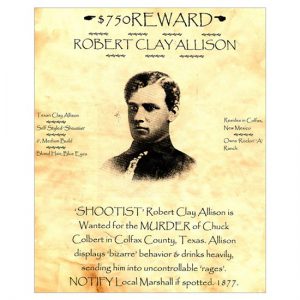

Sunday, September 13, 1875 was Tolby’s day to preach in Elizabethtown, around 25 miles from his home in Cimarron. His wife Mary and their two daughters had stayed home. Mary expected his return the Monday, probably no later than late afternoon. He didn’t return Monday and early on Tuesday Mary had become worried and requested a search party. Rev Tolby was found dead, shot twice in the back and hidden behind some brush. His horse, saddle, and other personal items had not been touched so it had clearly not been a robbery. Tolby’s many friends throughout Colfax County were furious. Even Clay Allison a local rancher and a noted gun fighter who had fought for the Confederats during the Civil War was furious. The two men were unlikely friends, but Tolby had the sort of personality that drew people to him. Allison has been described as a man with a temper and the personality of a Honey Badger. Once asked what he did for a living he replied, “I’m a shootist.” Lots of people were afraid of him, and with good reason. Clay was a man who went to extreme lengths to extract retribution when he felt he had been slighted or wronged. His Bible Belt upbringing demanded a settling of scores for the death of a Methodist minister who was also his friend.

The “cold war” that had been going on since Maxwell sold the grant to the foreign investors had entered a new, and much more dangerous phase.

Besides Clay Allison, who did not need much of an excuse to settle a score, Reverend Oscar P McMains took up the mantel of leading a “holy war” to break the backs of the Maxwell Grant owners. He was quoted as saying “The war is on..no quarter will be given for the foreign land thieves and their hired assassins”

Within two weeks rumors began to circulate that Cruz Vega the man who hauled mail from Elizabethtown to Cimarron and was the new Cimarron constable, was involved in the murder. On the evening of October 30, 1875 a masked mob who were said to have been led by McMains and Allison confronted Vega. He denied having had anything to do with the murder and pointed the mob toward Manuel Cardenas. The mob didn’t believe Vega. He was pummeled and then hung from a telegraph pole. Ten days later Cardenas was arrested in Elizabethtown and questioned. He said Vega had shot the minister and in addition he pointed the finger at two men who were members of the Santa Fe Ring named Mills and Longwell and said they were behind the killing.

Mills barely escaped a furious mob in Cimarron but was later arrested. Longwell had escaped to Fort Union just ahead of the Allison brothers. In the meantime Cardenas was still being held in Elizabethtown and transported from the jail to the office where he was being questioned. One night as he was being returned to the jail he was shot by person(s) unknown. Violence was out of control around Cimarron and for weeks the town was in the hands of a mob. In the months after Tolby was killed it has been estimated that as many as 200 others lost their lives in Colfax county in the aftermath of Tolby’s murder.

Wallace had his hands full, just as the Colfax County war was beginning to cool down another range war was heating up in Lincoln County which at that time was the largest county in the country, consisting of nearly the entire southeast quarter of the state. Billy the Kid was actively involved in that mess.

AFTERWARD

Although a substantial reward was posted by New Mexico in addition to a second reward posted by the Masonic Lodge and other friends in Cimarron the murder remains unsolved to this day.

Governor Wallace finished his novel Ben Hur in 1880 during his time in New Mexico. He resigned as governor in March 1881. In May of 1881 he was appointed Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, a diplomatic post he remained through 1885 after which he returned to his home in Crawfordsville.

The ghosts of Cimarron may have followed Mary Tolby and her children back to Indiana. In 1911 Grace Tolby, the youngest Tolby daughter was committed to Central State Hospital. She had been seeing and hearing spirits or angles who had come to disturb her and she had frequent conversations with said spirits, sometimes becoming violent, screaming and throwing things at the spirits. One has to wonder if her early girlhood experiences in New Mexico were the cause of her later insanity.

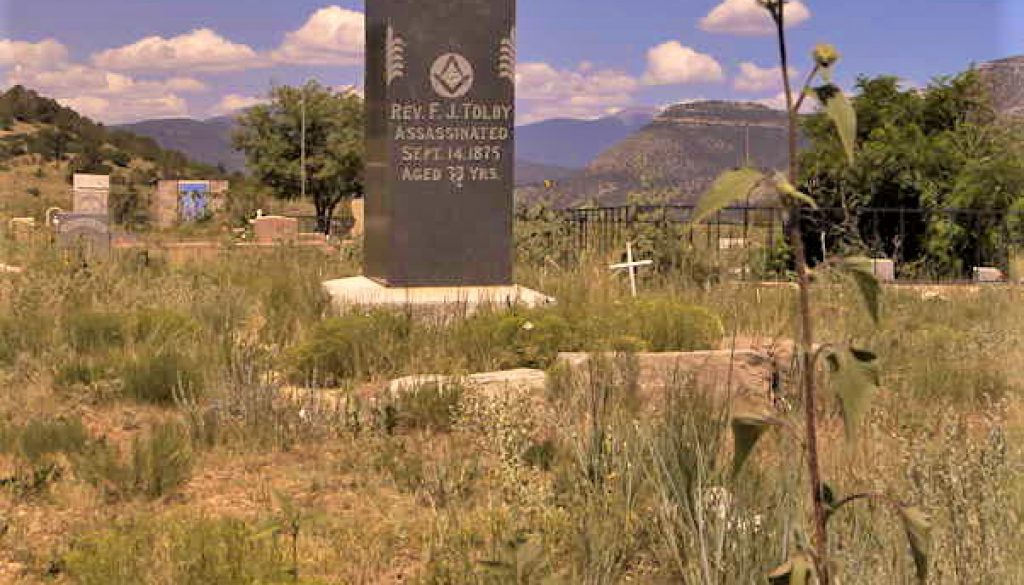

In 1913 the Cimarron Masonic Lodge dedicated a large new monument over the grave of Rev. Tolby which is a reminder of his life, yet today.