German-Americans in Tippecanoe County and the Great War

Cultural Attack on the Home Front

By Guest Blogger Mary Anthrop

“Every day is like Fourth of July and I am in the midst of one of the greatest battles of history. During the past week we have averaged about four hundred prisoners…. It appears as though Germany is making its last stand. Some of the prisoners are but sixteen years of age while others are fifty. They are without helmets and when asked what had happened to their head armor replied the Germans were using them to make ammunition.”

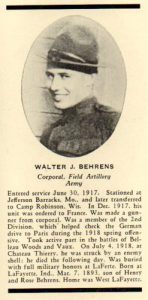

Corporal Walter Behrens to William Phillips, June 19, 1918

Shortly after writing this vivid account of the last days of World War I, Behrens of West  Lafayette, Indiana was mortally wounded in battle. He died July 5, 1918. Behrens, 25 years of age, was one of the first to volunteer when the United States declared war against Germany in 1917. He was assigned to the 17th Field artillery of the regular army. Behrens graduated from St. Boniface Catholic School, clerked in several groceries and before his enlistment worked as a stationary engineer at the Bohrer brewery and the American laundry. The West Lafayette community also knew him a natural baseball player. He was a “hard hitter” and ranked as one of the best catchers in the Lafayette Baseball League.

Lafayette, Indiana was mortally wounded in battle. He died July 5, 1918. Behrens, 25 years of age, was one of the first to volunteer when the United States declared war against Germany in 1917. He was assigned to the 17th Field artillery of the regular army. Behrens graduated from St. Boniface Catholic School, clerked in several groceries and before his enlistment worked as a stationary engineer at the Bohrer brewery and the American laundry. The West Lafayette community also knew him a natural baseball player. He was a “hard hitter” and ranked as one of the best catchers in the Lafayette Baseball League.

As one of the over 2000 men and women from Tippecanoe County, who served overseas during World War I, his story may not seem atypical. Behrens, however, was the grandson of German immigrants. German-Americans during the Great War engaged in home front activities and served overseas in the United States armed services. Yet even as German-Americans demonstrated their loyalty to the United States, they faced attacks on their heritage from their adopted country.

German-Americans in Tippecanoe County

Indiana had a smaller percentage of immigrants than many other states, yet the German immigrant population was large enough to impact the development of Indiana. The majority of German immigrants came to Indiana in the nineteenth century and by 1990 over 2 million Hoosiers claimed German ancestry. Indiana ranked ninth in the nation in the number of people who claimed German ancestry.

In Tippecanoe County in 1880, for example, nearly 2000 people were German born. The German presence existed in religious congregations, schools, a hospital and businesses. Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Jewish congregations of German heritage established churches and schools by the mid-1800s, including: St. James German Lutheran Church and School, St. Boniface Catholic Church and School, German Methodist Episcopal Church, German Evangelical Church, and Congregation Ahavis Achim Synagogue. In 1875 Mother Theresia Bonzel of the Sisters of St. Francis of Perpetual Adoration sponsored five Sisters from Germany who opened a hospital, St. Elizabeth, in the North-End of Lafayette and later staffed St. Joseph Orphanage and St. Ann, St. Boniface and St. Lawrence Schools.

Popular opinion believed German-Americans to be hard working and thrifty. German-American entrepreneurs engaged in diverse operations in Tippecanoe County. Successful business ventures included: breweries –Thieme and Wagner Co., Newman and Bohrer; jewelry store – Herman B. Lodde; groceries – John Reitemeier, Adolph Schwarm and John J. Heinmiller; hotel – John Lahr; bakery – John B. Ruger; merchants – Loeb and Oppenheimer families.

Although Tippecanoe County’s German-Americans represented the many different independent states before German unification, they embraced their common ethnic heritage. The German immigrants promoted the continued use of the German language in their churches and schools and in newspapers, such as Deutsch-Amerikaner (1874-1904). Religious societies, such as the St. Joseph Society of St. Boniface, and social clubs were popular. In 1854 German-Americans organized a “Turner” Society, in 1867 Siegel Lodge 273 of IOOF and the Deuscher Verein (German Club) in the early 1900s. German-Americans also bought a 10-acre plot two miles east of Main Street along the Wabash River and established a private recreational area – German National Park.

German-Americans also demonstrated their loyalty to the United States well before World War I. During the Civil War 50 German-Americans from Tippecanoe County volunteered to fight for the Union cause by enrolling in the 32nd Indiana Regiment. They engaged in politics. Louis Kimmell was a three-time mayor of Lafayette in the 1870s. During the Civil War Kimmell served as a second lieutenant of the 32nd Indiana Infantry Regiment.

German-Americans and World War I

When World War I erupted in 1914, German-Americans in Tippecanoe County expressed concern and sympathy for the people of their homeland. The Deutscher Verein (German Club) organized a relief for widows and orphans. German churches, societies and individuals contributed to the fund, while the local papers printed the names of donors to promote participation in the effort. The Deutscher Verein also protested anti-German newspaper stories that they believed to be British propaganda. The outcry convinced the local papers to periodically print editorials from an Illinois German-American newspaper.

Although they embraced their ethnic heritage, German-Americans professed loyalty to the United States. When the United States entered the War in 1917, the German churches, schools and societies participated in Red Cross, Liberty Bond and Thrift Stamp drives. They held public programs and exhibitions of loyalty and patriotism. St. Elizabeth Hospital in Lafayette, a motherhouse for an order of German nuns, offered its facility to convalescing American soldiers. Like native-born civilians, German-American citizens knitted socks, planted victory gardens, conserved food and fuel.

The greatest sacrifice of German-Americans, like native-born Americans, was to send their sons to serve in the armed services. In rural Tippecanoe County John, Michael and Henry Obermeyer, whose grandmother spoke to them only in German, served in France. Henry perished in France. Walter Behrens and William J. Memmer of West Lafayette were early volunteers. Behrens died of battle wounds in July of 1918 and Memmer died from an automobile accident in New York City. Their grandparents were German immigrants. Herman and William Maneke of Lafayette served in France; the United States government required their elderly German parents to register as “alien enemies.”

German born, Sister M. Camilla Zolper of St. Elizabeth Hospital, died of influenza after nursing infected soldiers. A popular and public figure of the hospital, Sister M. Camilla came to Lafayette in 1898. Camp Purdue sent military guards to St. Elizabeth as she lay in state. For her burial a procession of sixteen soldiers marched by the hearse, preceded by a detachment of soldiers and the Purdue Military Band. The Red Cross Motor corps transported the Sisters of the hospital to St. Joseph Cemetery. At the cemetery one of Camp Purdue’s buglers played taps. Sister M. Camilla was Tippecanoe County’s only female casualty of the Great War.

War on German Culture

When the United States entered into the War, government efforts to encourage patriotic participation intensified. Influenced by British propaganda, the Committee of Public Information demonized the enemy. Posters depicted the German enemy as cruel and heartless brutes. Overtime the United States required German born immigrants, who had never been naturalized as American citizens, to register as “alien enemies.” Men and women submitted four small shoulder and full face photographs and provided their height, weight, distinctive facial marks, and the color of their eyes and hair. In Lafayette a local paper published the names and addresses of the male “alien enemies.”

Native born citizens were encouraged to note suspicious behavior of German-Americans and pressure them to express their loyalty. Local patriots in Tippecanoe County organized a branch of the Indiana Patriot League. Thirty prominent men pledged to identify any traitor in their midst, to strike out the word “German” from every organization, church or society, to frown upon all things German, to remove the German language in schools, to encourage the sale of Liberty Bonds and Thrift Stamps and to spread the slogan “America for Americans.” In April 1918 the Deutscher Verein unanimously voted to change their name to the “Lafayette Liberty Society” and publicly pledged their “untiring support to every possible patriotic action in the furtherance of all governmental requests.”

In the final days of World War I “super” patriots attacked the use of the German language in newspapers, schools, and churches. The local Patriot League resolved to keep out of the community any papers printed in German. The public school boards debated for months the teaching of German in the high schools. Despite the opinion of the National Council of Defense that encouraged the study of German for its economic and military value, by September 1918, no Tippecanoe County school taught German. Despite the hardship incurred among its elder members and foregoing the future transmission of its culture to a younger generation, the St. James Lutheran and the St. Boniface congregations made a difficult decision. To avoid any doubt of their loyalty, they abandoned the speaking of German in their church services and their school instruction.

In 1919 the St. Boniface congregation dedicated a Memorial Vault in its North-End cemetery. A plaque on the vault contained the names of young men of German descent, who lost their lives in the Great War. Walter Behrens’ name appeared on the tablet. Now 100 years after the end of World War I, it is fitting to remember and honor all soldiers who gave the ultimate sacrifice of their lives for their country. Yet Behrens’ death, as a German-American, should also recall the loyalty and devotion hyphenated Americans had for their adopted country. German-Americans during the Great War not only suffered the sacrifice of their sons in battle, but at home experienced suspicion, fear and prejudice as “alien enemies,” a loss of their civil rights and an end to many of their German-language and cultural institutions.

For Further Reading

Giles R. Hoyt, “Germans,” in Peopling Indiana: The Ethnic Experience (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1996), 146-177.

Paul J. Ramsey, “The War Against German-American Culture: The Removal of German Language Instruction from the Indianapolis Schools, 1917-1919,” Indiana Magazine of History, Vol. 98, No. 4 (December 2002), pp. 285-303.